APPLYING DESIGN PRINCIPLES IN DIVERSE SETTINGS

Applying the design principles in daily practice requires commitment and capacity. Professional development supports are critical. Socializing, scaling and sustaining practices, however, often requires changes in structural design that make transformative, empowering, personalizing, culturally affirming experiences the norm. In schools, structural design changes—from advisories to co-teaching to the content of routine assessments— codify intentional shifts in how time, space, staff and resources are used to support redefined learning goals.

In community-based settings, the design changes needed are different and more varied. This is because the settings themselves are quite different from schools and varied from each other.

To understand this variation and discuss general implications for scaling and sustaining the design principles in community settings in ways that not only improve practice but could also strengthen connections with schools and other youth-serving systems, we tackle three questions. All are explored in relationship to five guiding principles of whole child design. They are:

- Why is there a need for dual playbooks —one for schools and one for community-based learning settings?

- How can community-based practitioners and system leaders—as well as young people, families, and school and community leaders—anticipate and optimize the diversity of these community- based learning settings?

- How can community-based practitioners and system leaders use the shared design principles as an opportunity to better connect with school leaders as both work to be more transformative, personalized, culturally responsive, and empowering?

Because the fundamental differences between community-based learning settings and schools make the opportunities and challenges associated with implementing the design principles very different.

Schools are very complex settings. When most of us think of schools, we think about classrooms. But we seldom stop there. We imagine a building or even a decentralized campus of micro-settings (classrooms, labs, cafeterias, libraries, outdoor spaces, music rooms, ball fields, gyms, hallways filled with bulletin boards and lockers). The size and quality of these settings changes, but our expectations are generally consistent and are reinforced in policies and budgets.

Communities are very complex settings. When most of us think about communities, we rarely think about classrooms first. We imagine an array of formal and informal places and spaces managed by different organizations and systems—libraries, parks and recreation departments, community-based nonprofits, civic and faith-based organizations, affiliates of national organizations like Boys and Girls Clubs of America, Communities in Schools, National Urban League—that support learning during and after the school day, in and outside of school buildings, and throughout the summer. (For a fuller discussion on the diversity of these settings, see A Typology of Community-Based Learning and Development Settings.) The variety of places and spaces throughout a community are similar to schools, but they are bundled together in many different combinations, supported by different organizations. Consider the combination of spaces you would expect to find within a community club (e.g., Boys and Girls Club), a local library, a recreation center, and a sleepover camp.

Learning and development settings are functional spaces (classroom, art room, gym/pool, Zoom group) made available by organizations that usually, but not always, have physical places (school, rec center, community club, performance spaces). These organizations recruit, train, and manage paid and volunteer staff who work with young people to co-create experiences in ways that are consistent with the practices and structures of that organization (or system).

Schools and school systems recruit many kinds of staff and manage many kinds of settings. But teachers and classrooms are the focal point for implementing practices and structures selected to achieve defined student learning goals.

The design principles playbook for schools is written with a deep understanding of the traditional conceptualization of the classroom and of school, with the explicit purpose of re-envisioning how these settings and the education system itself should be designed. The playbook lifts up practices and design structures using real-life examples of how schools are transforming from these traditional starting points working in ways that are scalable throughout fairly uniform systems.

Community-based settings, however, have always been anything but uniform. They are exceedingly diverse, in part, because they are highly flexible. This flexibility stems from a combination of factors, including: 1) participation is voluntary (young people and families “vote with their feet”); 2) content is not mandated (academic instruction may be a part of the programming, but is not required); and 3) accountability standards are not, for the most part, linked to dedicated public funding. Unlike schools, they do not have extensive structures at the local, state, and federal level focused on accountability for academic credentials and success. While this flexibility comes with challenges related to capacity and sustainability, it also encourages innovation, adaptation, and authenticity. For a further exploration of the structural differences and dynamics across schools and community-based learning settings, see Common Elements that Vary Across School and Community Settings.

As we worked with advisors to create this playbook, we quickly recognized the need to articulate both how the design principles illuminate the goals and strategies adopted by so many community-based learning settings, and why community learning settings would benefit from a playbook that is different than the one for schools.

Here are our answers:

- Taken together, the design principles are integrated non-negotiables for every setting and every organization that claims to support learning and development. If settings, organizations, or systems that support them are “in the red” on any element (implementing practices and policies that actively go against the principle), not only is learning threatened, but it is possible they are doing harm.

- Taken separately, the design principles often reflect the primary purpose or top priorities of each system or organization. No organization or setting should be in the red, but few, if any can honestly argue that all five principles are their top priorities. Schools lead with content mastery. Mentoring programs lead with relationships. STEM and arts programs lead with activity- rich experiences. Character organizations lead with building skillsets, mindsets and habits. Multi-service organizations lead with access to integrated supports and services. This variation of emphasis also applies to specific settings and adults within organizations (e.g., the counselor may be more focused on supports and services, the coach on building skillsets, mindsets and habits).

- The diversity across community-based settings and organizations of what guiding principle they lead with makes it difficult to offer general recommendations for design structures. One setting or organization’s weakness could well be another organization’s strength. In this playbook, you will find program and organizational examples that may lead with a particular principle, but are intentionally thoughtful about the integration of all five.

By giving ways to unpack and take stock of the “raw materials” that make up the learning experience—the adult leader(s), the setting, and the young people.

Since the structure and composition of community programs vary widely, putting the science findings into practice requires understanding and embracing the diversity of settings so that practitioners—regardless of where they operate, whom they serve, and what they do—“see themselves in the science”.

The main reason community-setting practitioners and administrators should be encouraged to look at all of the raw materials they are working with—ideally in consultation with young people and their families—is that they often have more freedom than traditional systems to flexibly respond in ways that optimize how these elements come together to create powerful learning experiences.

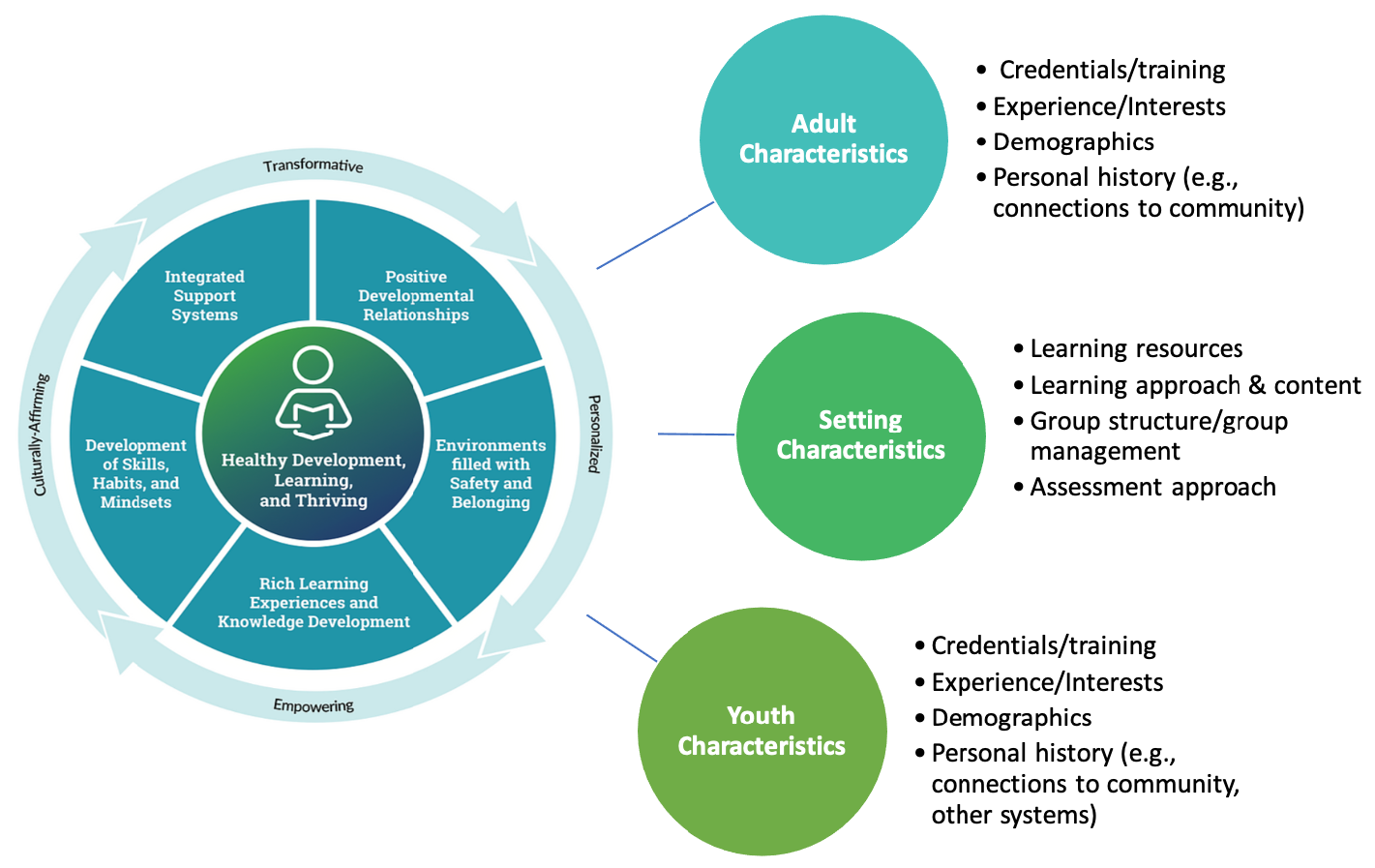

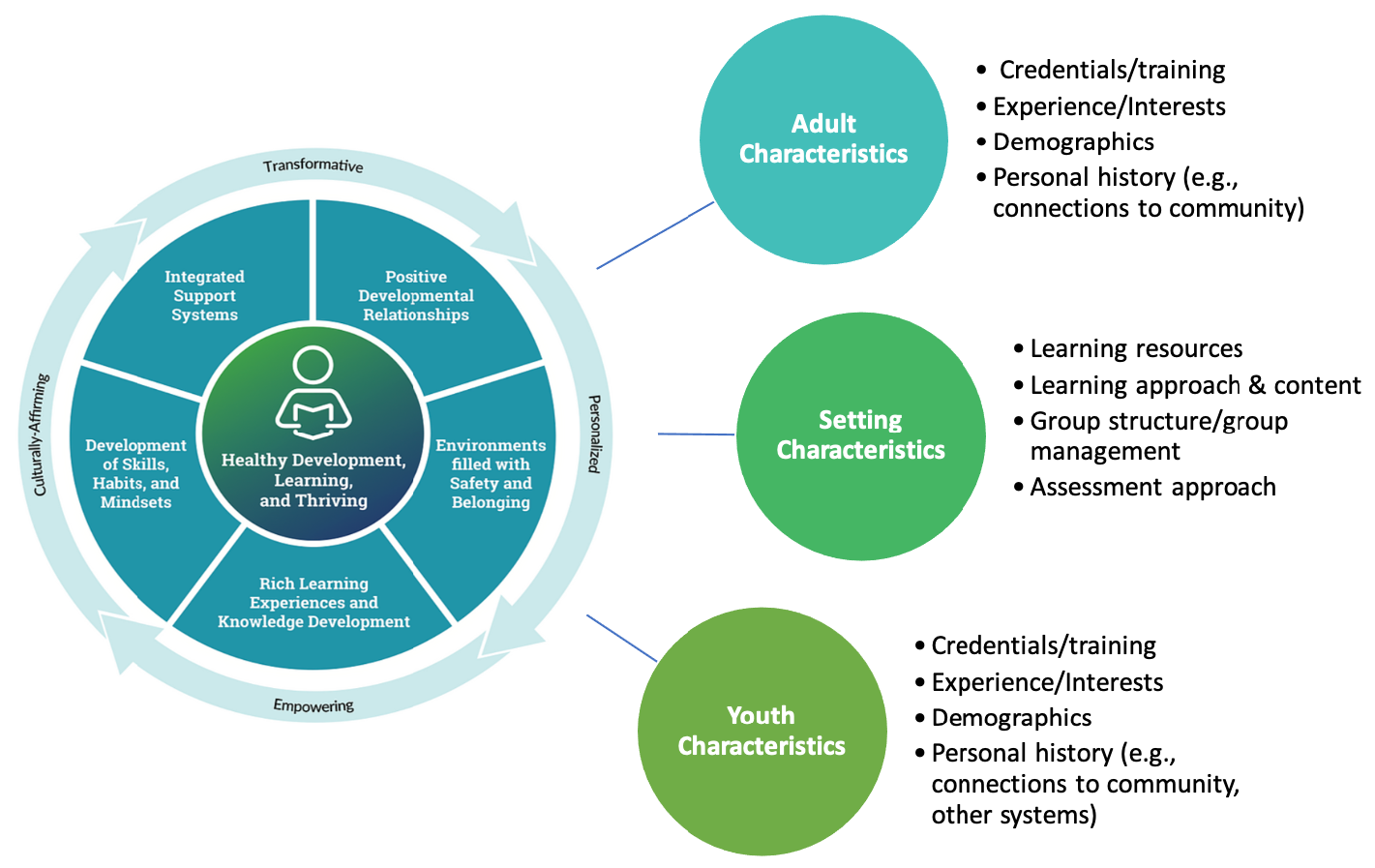

Three elements combine to influence the creation of the learning experience—the adults1 , the settings, and the young people and families that “vote with their feet” to participate.

As noted, community-based settings may be familiar- type spaces (classroom, meeting room, ball field, online groups), housed or linked to different places

(libraries, youth organizations, faith-based organizations, community centers, workplaces) that are associated with organizations that have different goals, rules, resources, and approaches. It is precisely because generally adults, young people and families, if they chose to engage, can influence the shape of specific setting-level experiences that it is important for all actors—practitioners, administrators, youth and families—to have a firm understanding of their assets and constraints. Giving them explicit information about the elements that contribute to optimal learning, allows them to use the program flexibility and relational connections they have to deepen opportunities for meaning making2 by seizing moments.

Given parents and young people’s intuitive awareness of the importance of these design principles, the effort they make to look for these elements when selecting opportunities, and the high level of trust they have in the staff of these programs, it makes sense to engage them more explicitly in assessing and improving learning settings, including recommendations on how to scale and sustain supportive practices.3

By explaining how they activate these four broad commitments, and sharing successes and challenges associated with achieving equity and excellence.

These aspirational commitments for the systems and settings —transformative, personalized, empowering and culturally affirming—are the raison d’etre for many community-based settings. While many position themselves as supporting academic achievement, transference of academic content and credentialing of the “average student” are not their primary goals.4

In the K-12 education space, leaders are using these commitments to challenge traditional ways of doing business and rethink and redesign how they organize their staff, their resources and their schedules, and their spaces to meet those goals. In the community spaces, these goals are frequently their reason for being and often have been established in response to what they see as the inadequate response of schools and other systems.

Many of these community-based learning settings have been committed to transformative learning and development because they are working to counter what was seen as rote learning or harmful experiences that took place in schools or other systems. In particular, programs and organizations that work with young people who have been system-involved or experienced marginalization from systems work to not only transform the trajectories of these young people but, in many cases, work with young leaders to advocate for change in the systems themselves. Many are committed to culturally affirming experiences not only because they are often community grown and community embedded, but because of their sense that their young people aren’t seen and aren’t getting their identities affirmed in the school. They are committed to personalized approaches because they start with relationships, interests, assets, and needs. They are committed to empowering in ways that are not just about the agency of the learner in their own learning experience, but the agency of the young person in bringing about community and societal change.

They are not held accountable for a certain number of hours or credits. They have been created with the flexibility to lead with these principles and develop structures and infrastructures around these things.

That is not to say that this parallel space is by any means perfect but, put simply, the design questions are different. The overall picture is not equitable. Access and affordability are major issues. The offerings are frequently piecemeal. The quality is variable. The upside of the flexibility is that they have had more opportunity to be innovative and responsive. The downside is that they do not have the stable funding and infrastructure to support professional development and consistency or to sustain and scale their work in ways that every young person has access to high-quality, equitable learning and development experiences.

As the K-12 system steps up to meet these commitments —transformative, personalized, empowering, culturally affirming—there are decades of wisdom and expertise to mine from the practitioners in these community-based settings. As school leaders get to know the range of community-based organizations and programs in their community, it will help to not only understand the emphasis of individual programs but also to get to know the organizations and networks as a collective set of community assets. As a set of providers, what are they doing to be intentional—individually and as a field—to promote practices aimed at these commitments? How do they manifest being culturally responsive? How do they personalize? How do they empower? How are they transformative? Starting with these fundamental questions—as well as a nuts and bolts understanding of the differing factors that shape how K-12 systems and community-based settings operate—will illuminate where there are opportunities for partnership and shared responsibilities that move beyond the transactional (space, transportation, time coverage) towards more shared understanding of purpose, expertise, and approach.

KEY RESOURCES FOR IMPLEMENTING DESIGN PRINCIPLES IN COMMUNITY-BASED SETTINGS

The David P. Weikart Center for Youth Program Quality (Weikart Center) has tools, resources, and research to help community-based settings create safe, supportive, relationship-rich learning environments that offer opportunities to develop critical skills, mindsets and habits.

Preparing Youth to Thrive and Preparing Children to Thrive, created by the Weikart Center with the Forum for Youth Investment, are field guides that provide case studies of exemplary community-based learning and development opportunities and how they create structures and opportunities that support whole child design in school-age and adolescent settings.

Ready by Design: The Science and (Art) of Youth Readiness, developed by the Forum for Youth Investment, provides a synthesis of the existing research—including new findings in brain science as well as trends in social emotional learning, 21st century skills, employability skills and childhood well-being—into a systems-neutral compendium.

Thriving, Robust Equity, and Transformative Learning and Development, co-authored by Readiness Project Partners, leverages recent syntheses of the science of adolescence, the science of learning and development, and the impacts of institutionalized inequities to emphasize the fact that all children and adolescents can realize their potential and thrive.

How Learning Happens Edutopia video series illustrates strategies that enact the science of learning and development in schools and community-based settings.

Aspen Institute’s National Commission for Social, Emotional, and Academic Development’s reports provides a research agenda to support whole child and adolescent development across learning settings, offers strategies for how school and communities can create learning environments that foster comprehensive development of all young people, and discusses the role of policy in creating conditions for communities to implement locally crafted practices that drive more equitable outcomes. Reports include Building Partnerships to Support Where, When, and How Learning Happens which describes the critical role that youth development organizations play in supporting whole child development, in partnership with schools.

The University of Chicago Consortium on School Research offers a developmental framework for youth development from early childhood to young adulthood, with an emphasis on the kinds of experiences and relationships that foster the development of factors that influence success.

1Eccles, J., & Gootman, J. (Eds.). (2002). Community programs to promote youth development . National Academies Press.

1Eccles, J., & Gootman, J. (Eds.). (2002). Community programs to promote youth development . National Academies Press. *You could also think of these as “learning leaders” – in many community settings the designers of the learning and engagement experience are teenagers and young adults as frequently as older adults.

2Immordino-Yang, M.H., & Knecht, D.R. (2020). Building meaning builds teens brains. https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/ building-meaning-builds-teens-brains

3Learning Heroes. (2021). Out-of-school time programs this summer: Paving the way for children to find passion, purpose & voice. Parent, Teacher & OST provider perceptions. https://r50gh2ss1ic2mww8s3uvjvq1-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp- content/uploads/2021/04/Finding-Passion-Purpose-Voice-May6.pdf.

4Learning Policy Institute & Turnaround for Children. (2021). Design principles for schools: Putting the science of learning and development into action .