INTEGRATED SUPPORT SYSTEMS

THE OASIS CENTER

The Oasis Center , a non-profit youth organization deeply rooted in the Nashville, Tennessee community, connects young people and their families to systems of supports that best meet their needs. The center seeks to empower youth in their personal lives and collaboratively create justice and equity in the institutions that impact them. The Oasis Center does this through more than 20 programs and services based on a foundation of four areas of youth success: safety, belonging, empowerment, and generosity.

Serving young people from middle school to young adults, the Oasis Center operates in two modes—crisis intervention and essential supports and youth leadership and empowerment. A young person can come through one door—the need for transitional housing services, for example, and get connected not only to a permanent housing plan and counseling, but youth development programming, coordination with the school, and later, leadership development programming, thus coordinating the right set of integrated supports for each young person and their family.

“We have had young people come in through our 24-7 emergency shelter program in which both the young person and their family participates in a two-week overnight structured program where they are connected to a case manager, develop an action plan to stabilize their living situation, participate in family counseling, and establish a six-month follow up plan,” Oasis youth manager Justin Aparicio explains. “And we are also in their schools, more often than not, making connections back to the school for extra support.”

Because there are multiple doors into Oasis Center, that same young person can feed into social action and activism on some of the very issues that brought them to Oasis Center through the center’s Action, Advocacy, and Education programming, a ladder of leadership development and civic action programs that provide young people with skills to take action on issues that affect them and their communities.

As an outcomes-driven organization, Oasis Center monitors its results. The 2019 Annual Report indicates that the Oasis Center:

- Helped 2,455 students from middle school to college improve access to higher education through 1-on- 1 support, group workshops, ACT prep, and college retention services. Nearly 70% of first-generation college students participating in Oasis Resource Centers at Nashville State Community College (NSCC) stayed in college—a rate 30% that’s higher than their peers at NSCC.

- Provided therapeutic support for 320 youth and 562 family members. At 3 months, 80% of clients reported improvement in the problems that brought them to Oasis.

- Worked statewide with 23 foster care and juvenile justice sites to get youth involved in their communities through the Teen Outreach Program (TOP). As a result, 1,530 youth across the state engaged in TOP, building their life skills, healthy behaviors, and sense of purpose.

For more information about how the Oasis Center contributes to an integrated systems of supports for youth and families, visit: https://oasiscenter.org/

OVERVIEW OF INTEGRATED SUPPORT SYSTEMS

All children and youth have unique assets and interests to build upon in their learning journeys. All children also experience challenges that need to be addressed without stigma or shame to propel their development and well- being. These challenges can result from personal or family struggles or adverse childhood experiences, such as discrimination, food or housing insecurity, physical or mental illness, or other difficulties and inequities.

Research has documented that well-designed supports such as those provided by the Oasis Center in the opening vignette can enable resilience and success even for youth who have faced serious adversity and trauma. These supports include everyday practices that communicate to young people that they are respected, valued, and loved, as well as specific programs and services that prevent or buffer against the effects of excessive stress.

The situation facing young people, families, educators, and community-based practitioners today underscores the importance and urgency of this endeavor. The challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic, racial injustice, and economic uncertainty are omnipresent and acutely felt, particularly by Black Americans and other communities of color. Orchestrating integrated supports that systematically assess young people’s comprehensive needs and strengths and coordinate resources in a unified and collaborative way is essential. Such a system can mitigate barriers, enhance coping, strengthen resilience, re-engage disconnected learners and their families, and help reduce the opportunity gaps.

Effective learning environments take a systematic approach to promoting development in all facets of the school and its connections to the community. A well designed and implemented support system weaves together school and community resources to enhance equity of opportunity for success at school and beyond. It provides assistance vital to social and academic success in learning settings and connects young people and families to services that promote holistic development as well as additional opportunities to learn. Further, such supports can promote agency by helping young people discover what motivates and inspires them to meaningfully contribute to their community.

WHY ARE INTEGRATED SUPPORT SYSTEMS IMPORTANT? WHAT THE SCIENCE SAYS

WHAT CAN COMMUNITY-BASED SETTINGS DO TO FOSTER INTEGRATED SUPPORT SYSTEMS?

Most children experience adversity in some form at some point in their lives and need opportunities for learning and supports that enable them to thrive. Indeed, each year in the United States, at least 46 million children are exposed to violence, crime, abuse, or psychological trauma, representing more than 60 percent of the total.1 Thus, learning environments need to be set up with many protective factors, including health, mental health, and social service supports, as well as opportunities to extend learning and build on interests and passions, integrated across the many settings where young people spend their time.

How to Foster Integrated Support Systems

- Connect youth to supplemental learning opportunities

- Promote access to other supports and opportunities that foster health and well-being

Community-based learning and development settings contribute to integrated support systems in two primary ways: they help children and youth access supplemental learning opportunities that contribute to academic growth, and they promote access to other supports and opportunities that foster health and well-being. Unlike a school setting that strives to bring services into the building, community-based settings may bring supports into the setting but they also may serve as a resource and referral support to families, bridging connections between youth and family needs and services at other settings across the community—health centers, public assistance agencies, and other community-based learning and development opportunities.

Connect Youth to Supplemental Learning Opportunities

At the center of a well designed and implemented system of supports are structures and practices that enhance learning—to provide academic and non-academic supports that foster growth, to offer opportunities for academic and social enrichment, and to remove barriers to learning and development. Community-based learning and development settings are, by nature, set up to enhance learning through offering supplemental learning opportunities, thereby being a valuable asset as part of a seamless and aligned system of supports for young people. Many afterschool programs offer homework help and academic enrichment. Specialty programs such as STEM and robotics can enhance young people’s understanding of key mathematic concepts through hands-on experiential learning. Further, extended learning time programs provide opportunities where youth can engage in enrichment activities and receive academic support during out-of-school time. When used well, these opportunities can accelerate learning and reduce opportunity gaps between what youth from low- income families and their peers from middle- and upper- income families experience during out-of-school hours. However, additional time will not in and of itself promote positive outcomes; additional learning time must be high quality and meaningful in order to move the needle on student achievement and engagement.2

Community-based learning and development settings’ efforts to supplement and enhance learning are strengthened when key practices are in place.

HIGHER ACHIEVEMENT

Higher Achievement in Washington, DC utilizes 21st Century Community Learning Center funds to support middle school student learning during out-of-school time through small group, academic instruction afterschool and during the summer.

Higher Achievement creates unique, grade-level curricula aligned with district curriculum standards to ensure learning during out-of-school time complements and aligns with learning happening during the school day.

When preparing to launch Higher Achievement in a new state or district, the Curriculum Associate conducts a correlation assessment between existing Higher Achievement curricula and the English/language arts and math standards for that state/district. Following the correlation exercise, Higher Achievement may develop new curricula to ensure that mentoring sessions will align with the school day lessons students are learning. As changes to the standards occur, Higher Achievement standards correlation documents are revised accordingly.

Through review of report cards and conversations with parents, Higher Achievement Center Directors prioritize scholars who are in greatest need of individual support and request conferences with those scholars’ school teachers. These are accomplished during a teacher’s planning period, after school, or during parent/teacher conference days held at the school.

During these conferences, the Center Director talks with the teacher to learn specifically how the child is struggling and then work with the teacher to identify ways that Higher Achievement can best support the child. The Center Director communicates with the scholar’s parent(s) when these conferences are taking place and attempts to include the parent(s) in the conversations whenever possible. At the time of enrolling their child in Higher Achievement, each parent signs a waiver that grants Higher Achievement staff access to the child’s school records and teachers for such conferences.

Key Practices to Connect Youth to Supplemental Learning Opportunities

In order to understand the strengths and needs of all youth, schools, and community partners need a collaborative process to help them learn from and leverage the insights of diverse members of the learning community. There are multiple ways to accomplish this, but the goal should be to include representation from young people, families, educators, and community partners (e.g., early childhood, after-school, extended learning, and youth development programs, as well as mental health providers) to plan for and tailor academic, social, and emotional supports based on the specific experiences of each learner.

High quality after-school programming is a core strategy for connecting youth to supplemental learning opportunities. There are several factors that make after-school programs more impactful—one of which is alignment with a school’s learning goals and approach . When after-school programs further and reinforce a school’s curriculum, pedagogy, and core values, they are more effective in supporting youth outcomes, growth, and engagement. Indeed the 21st Century Community Learning Centers initiative, the only dedicated federal fund for after-school programming, provides over 1.7 million youth in kindergarten through 12th grade the opportunity to engage in hands-on experiential learning opportunities that enhance academic growth. National evaluation results indicate that youth who regularly participate in 21st Century Community Learning Centers improved their school attendance, school engagement, health-related behaviors, and math and reading achievement.3

Community partners can offer expanded learning time (ELT) that engages deeper learning pedagogies with content that is connected to youth’ lives outside of school .

Collaboration does not happen without dedicated staff time devoted to ensuring effective school-community partnerships to support learning. Partnerships require an intentional outreach and engagement strategy, with resources dedicated to nurturing and maintaining partnerships. Even when schools have community partners and programs, they typically operate in silos and are not well-aligned with the school’s academic plans and goals. As described below, community schools are one approach to aligned partnerships where coordinators facilitate and provide leadership for the collaborative process and development of a continuum of services for children, families and community members within a school neighborhood. In some instances, partnerships are coordinated by a family resource center or an afterschool site coordinator. Regardless of who coordinates the partnerships, they need to be strategic and data driven so that partners have access to the information and data they collect about youth so they can better align supports across settings.

A key aspect of creating a strong system of learning support is to develop systems and practices that support the identification of learning challenges and assets, which can allow educators and community practitioners to understand what supports may be needed. Community-based learning and development settings will be more impactful and effective in supporting youth’s growth when they have easy and regular access to shared data so that they can monitor youth academic progress. Accessing school data generally requires data sharing agreements between community partners and the district.

Student data is protected under a federal law called the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA). In order for a community partner organization to have access to any protected student data, they must sign a data-sharing agreement with the school system, their staff/volunteers much complete a FERPA training and sign a confidentiality form, and students’ parents must provide consent to permit the school to share data with a specific organization.

The Early Warning and Response System, utilized by United Way of Asheville and Buncombe County and its community partners, automatically pulls data from the schools’ database so that teams of teachers, counselors, and social workers can immediately identify students who are slipping off track, identify the underlying causes of why a student is off track, put in place targeted interventions, and track progress. This data is presented in an easy-to-read dashboard format. The dashboard can show individual, school, and systems-level data for use by a teacher working with an individual student as well as a superintendent searching for important trends that need to be addressed. Early results show significant growth in family and community engagement and in students accessing services—precursors to student achievement gains.

Sharing data across partners can be facilitated by an out-of-school time intermediary such as the Denver Afterschool Alliance. Denver Public Schools (DPS) has a partnership with the Denver Afterschool Alliance (DAA), a network of over 300 afterschool and youth development organizations, to share school data with afterschool programs in order to better design and implement programs to support DPS students. Three factors were deemed critical to the success of establishing data sharing agreements: willingness of legal counsel of school districts to grant sharing student data, champions in the both the school and the youth development sector that advocated for data sharing, and leadership at the district level that believed youth development was integral to achieving a whole child vision.7 As a result, DAA providers have access to data on school attendance, suspensions, and standardized test results for students who attend their programming, benchmarked against the entire district. Providers are then trained on how to interpret their program’s results for program improvements.

Another way to monitor a young person’s progress is for community-based settings to gain access to school data portals in order to monitor how youth are doing in school. Some community partners have taken this approach as they operate remote learning hubs so that they can identify learning needs and challenges and connect youth to the supports they need to be successful.

When Richmond Public Schools closed in March 2019 due to COVID-19 the Boys and Girls Clubs of Metro Richmond (BGCMR) ramped up efforts to ensure that its Club members were getting the learning and development supports they needed. Because they had parent/guardian permissions to access and receive Club member data as part of the Club membership agreement, BGCMR staff were able to gain access to student portals allowing them to immediately see assignment status/standing, grades and attendance in remote learning. Staff used their access to data to create and execute plans to support youth that were off-track. Staff continued to engage with on-track youth but off- track youth gained more attention as they were focused on getting them re-engaged with their education.

A major change for BGCMR as a result of being able to access the data was that BGCMR invited its Club members with the most need back into its buildings to re-establish relationships. Having the students in the building and being able to see what they were experiencing in virtual class plus access through student portals allowed BGCMR staff to have a more well-rounded view of what was driving the lack of engagement to school. This access also created an accountability platform with students and their families.

Community-based practitioners can add capacity to the school day to help youth gain access to more role models and caring adults that can support their learning and development. The Men’s and Women’s Leadership Academy (MWLA) in Sacramento City Unified School District’s (SCUSD) is an effort to intentionally combat the school-to-prison- pipeline for underserved low-income students of color by creating supportive and productive learning environments. Male and female mentors come into district high schools and middle schools to teach leadership and life skills to at-risk young men and women. The district has found that students who participate in the academy show improvement in grades, attendance, and graduation rates.8 City Year helps high- need schools close gaps by supporting youths’ academic, social, and emotional development in classroom and whole school settings. It deploys teams of AmeriCorps members to bring developmental frameworks, social emotional assessments and progress monitoring resources to review with teachers in combination with information such as grades, homework completion, academic assessment. The holistic intervention approach informs responsive strategies for whole child academic growth and improvements in school culture and climate.9 See below for more information about how City Year partners to add adult capacity to the school day.

THE CORPS FOR STUDENT SUCCESS FRAMEWORK

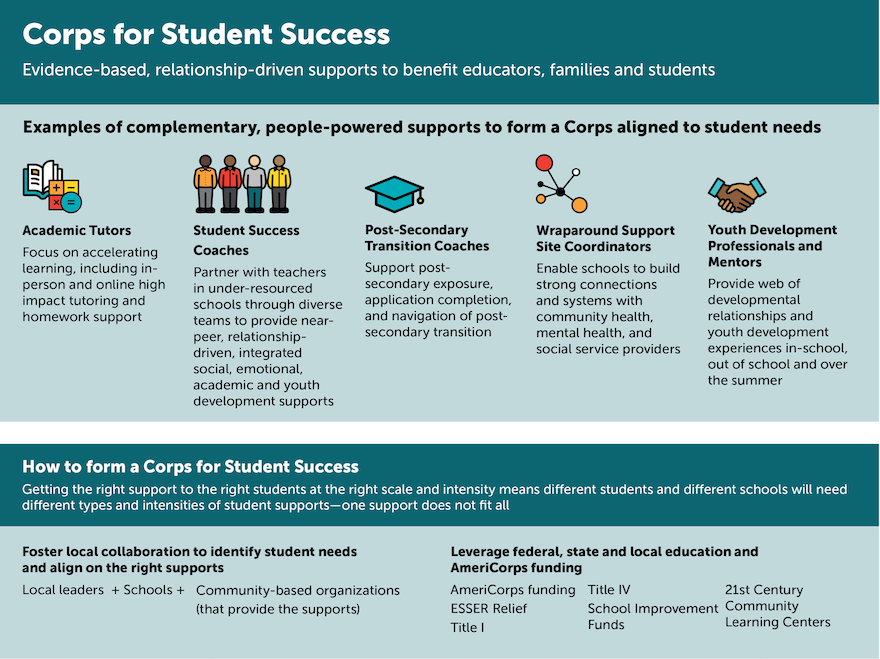

The COVID-19 pandemic has created unprecedented disruption to schooling for millions of students and has exposed and exacerbated inequities for young people our education system already underserved. City Year , the COVID Collaborative , and the Everyone Graduates Center have authored the Corps for Student Success Framework (Figure 14), a set of recommendations for educators, community leaders and policymakers to consider in selecting the right evidence-based, “people powered” responses to meet both short-term and long-term needs of young people.

The Corps for Student Success Framework is an organizing framework that elevates “people powered” learner supports that ensure all learners have access to the relationships, opportunities, and environments they need to learn and thrive. These supports include:

- Academic tutors,

- Student success coaches,

- College and career advisors,

- Wraparound support coordinators, and

- Mentors.

The framework emphasizes the need for responses to:

- Be locally driven, aligning local needs while harnessing community strengths

- Take a holistic approach grounded in the science of learning and development

- Be relationship focused, culturally, linguistically and ability affirming, and asset-based

- Be broadly available to respond to the pandemic, but focused on sustainably serving our most marginalized young people to build a more equitable education system in the long-term and

- Support or align with what is happening during the school day to accelerate student learning

As schools reopen this fall, there is an opportunity to bring this framework to life and enable more young people in communities across the country have access to the resources and opportunities they deserve to realize their potential.

For more information on the Corps for Student Success, visit http://www.pathwaystoadultsuccess.org/ studentsuccesscorps/

Promote Access to Other Developmental Supports that Foster Health and Well-Being.

Community-based programs are poised to cultivate a well implemented and sustainable network of partners such as health and mental health services and food and housing support services that can serve youth and family social, emotional, physical, and mental needs.

Awareness of the pervasiveness of toxic stress across the income spectrum and the growth of child poverty in economically and racially traumatized communities have created additional demands for health, mental health, and social service supports that are needed for children’s healthy development and to address barriers to learning. A comprehensive review of integrated student supports found that integrated support systems can support student achievement, and it highlighted community partnerships as a key lever for implementation.10

By supporting efforts to create integrated support systems community-based settings can help address the reality that children whose families are struggling with racial violence and poverty—and the housing, health, and safety concerns that often go with it—cannot learn most effectively unless their nonacademic needs are also met. The goal is to remove barriers to learning by connecting youth and families to the formal and informal assets of services in the community to support their overall well- being and growth.

Many of the ways that community-based settings connect youth to supplemental learning opportunities are also strategies to employ when thinking about a broader set of development needs. However, the primary ways that community-based learning and development settings connect youth and families to supports that foster healthy development and well-being are listed below.

ENGAGING AND SUPPORTING FAMILIES IN REDWOOD CITY, CALIFORNIA

Redwood City 2020 has transformed six of 16 schools in the Redwood City, California, school district into community schools. Each has a Family Resource Center, and one third of the families participate in the program. Parents not only receive services, but they are also offered a range of educational opportunities, become involved, and are empowered to teach other parents, creating a strong community. Many of the parents are immigrants with language barriers. But at the Family Resource Centers, they find a community of other immigrant parents who speak their language and play a leadership role in the schools.

Redwood City community schools work with their partners to engage communities and families to promote school readiness among children.

By creating community mobilization teams made up of family members, educators, and other community members who have participated in professional development programs, they enhance family-to-family education and outreach, preparing the community for success. As a result, the families of 70% of students in Redwood City community schools are actively engaged with school campuses through adult education, leadership opportunities, and school meetings. Students whose families participate consistently have shown positive gains in attendance and in English language proficiency for English learners.

Source: United Way Bay Area. (n.d.). Community schools: Redwood City 2020. San Francisco, CA: United Way Bay Area.

Key Practices to Connect Youth and Families to Other Developmental Supports

As noted above, community-based settings may bring health and wellness supports into the setting but more often they serve as a resource and referral support to families, bridging connections between youth and family needs and services at other settings across the community— health centers, public assistance agencies, and other community-based learning and development settings.

Indeed, throughout the COVID-19 pandemic this function has become more critical and more visible as adults in afterschool and other community-based learning and development settings have reached out to families about their basic needs, providing meal delivery service and connecting them to health care and public assistance resources.

When brokering a connection between a youth and their family and another organization or agency to receive additional supports, it is important to do a “warm handoff.” In clinical settings, the “warm handoff” is seen as a best practice for patients. In essence, it involves the transfer of care or responsibility between two members of a team. In a warm handoff, this transfer occurs in the presence of the youth and/or family. This creates transparency and better allows the youth to develop trust and engagement with the next member of the team.11

There are promising and proven models to ensure that community- based learning and development settings are viewed as part of comprehensive integrated support systems, namely Communities in Schools and Community Schools.

Communities in Schools (CIS) is a national dropout prevention program overseeing 2,300 schools and serving 1.5 million students in 25 states. For nearly 40 years, CIS has advocated bringing local businesses, social service agencies, health care providers, parent and volunteer organizations, and other community resources inside the school to help address the underlying reasons why young people drop out. CIS provides integrated student supports such as health screenings, tutoring, food, clothing, shelter, and services addressing other needs by leveraging community-based resources in schools, where young people spend most of their day. Some integrated student supports benefit the entire school community, like clothing or school supply drives, career fairs, and health services, while more intensive supports are reserved for young people who need them most. CIS places a full-time site coordinator at each school; the site coordinator is typically a paid employee of the local CIS affiliate (a nonprofit entity governed by a board of directors and overseen by an executive director). Working with the CIS national office, state CIS offices provide training and technical assistance to local affiliates, procure funding through numerous sources, and offer additional supports that enable capacity building for site coordinators at the local level.12

Another proven effective way to ensure that community- based learning and development settings are part of a comprehensive integrated support system is to adopt a community school mode. Community schools represent a place-based school improvement strategy in which “schools partner with community agencies and resources to provide an integrated focus on academics, health and social services, youth and community development, and community engagement.”13 Many operate year- round, from morning to evening, serving both children and adults. Community schools often have dedicated staff (i.e., community school director, family liaison) who support the coordination and sustainability of their various structures. Central to a community schools approach is the role that community-based partners play in partnering with schools and with each other to provide integrated, individualized supports to youth and their families.

Community schools offer integrated student supports, expanded learning time and opportunities, family and community engagement, and collaborative leadership and practices.14 These schools often draw on a wide range of community and cultural resources, including partnerships with families, to strengthen trust and build resilience as children have more support systems and people work collaboratively to help address the stresses of poverty and associated adversities children may face.

COMMUNITY PARTNERS ARE PART OF COMPREHENSIVE SUPPORTS

Communities in Schools of Central Texas supports social workers, counselors, and AmeriCorps members to work on school campuses within the Austin Independent School District and five surrounding school districts to provide direct support to students and to coordinate a network of social services, businesses, and community resources. Site coordinators and partners deliver supports to students and their families, from schoolwide services to targeted programs to intensive, wraparound supports. In Central Texas, that includes a partnership with the local housing authority to provide case management for students living in public housing as well as afterschool programming on site; a leadership development program for adolescent males; and an early childhood adult education center that enables parents to earn their GED or ESL certificate, along with a parenting curriculum, while their infants and toddlers receive care.

Community schools also have dedicated staff (e.g., community school director, family liaison) who support the coordination and sustainability of their various structures and programs. Community school personnel are typically part of the school leadership team and other governance bodies in the school. The community school manager or director generally conducts assets and needs assessments, recruits and coordinates the work of community resources, and tracks program data.15

Evidence shows that community schools can improve outcomes for youth, including attendance, academic achievement, high school graduation rates, and reduced racial and economic achievement gaps.16 17 18 A recent RAND study of New York City’s 250+ community schools initiative shows that community schools can work at scale. Promising results include a drop in chronic absenteeism, with the biggest effects on the most vulnerable students, and a decline in disciplinary incidents. Youth were more likely to progress from grade to grade on time, accumulate more course credits, and graduate from high school at higher rates.

GETTING STARTED WITH A COMMUNITY SCHOOL IN GRAND ISLAND, NEBRASKA

Grand Island, Nebraska is just getting started with community schools. In its pilot site, a designated community schools coordinator, the school social worker, and principal are working together to integrate support and services. The district coordinator is responsible for establishing the community partnerships, securing agreements, and scheduling the programming. District staff, from the office of Strategic Partnerships and Stakeholder Engagement, also support the work by assisting with translation services, working directly with parents to establish goals for their families, and on fulfilling requests for programming. With limited resources available, the community schools team focuses on bringing programs and services already provided by community partners into the school. Some of these partners are providing immunization clinics, dental check-ups, financial planning, healthy cooking, youth/child yoga, mindfulness meditation, and homework help. With the success of the pilot school, the district will open its second community school in school year 2020-21 following the same model.

Grand Island Public Schools: https://www.gips.org/departments/community-partnerships-and-engagement/ community-schools.html

SUMMARY

Community-based learning and development settings are part of the fabric of integrated support systems. They are often called upon to provide supplemental learning opportunities and add and expand adult capacity during the school day. They are also critical partners in helping youth and their families access a range of non-academic supports that contribute to whole child development.

Sometimes community-based settings connect youth and families on their own, and sometimes they are part of a coordinated approach to comprehensive and integrated support systems based in schools, with referrals to community-based partners.

For community-based partners to contribute to integrated support systems, adults who work across settings need to:

- Create a shared vision for learning and development for each youth

- Conduct joint, data-driven planning

- Commit to resources to fund a position dedicated to managing the partnerships.

TOOLS AND RESOURCES TO CREATE INTEGRATED SUPPORT SYSTEMS

- Building Partnerships to Support Where, When, and How Learning Happens provides a framework for broadening our understanding of where, when, and how young people learn, both in and out of school and during the summer. It highlights examples from across the country of local partnerships that support youth. Building Partnerships also recommends ways for educators, policymakers, and funders to partner with youth development organizations, capitalizing on formal and informal learning settings that support young people’s success.

- Building Partnerships to Support Where, When, and How Learning Happens Example Bank offers insights as to how youth development organizations are partnering with schools, other community organizations, districts, and states to expand where and when learning happens.

- Expanding Minds and Opportunities: The Power of Afterschool and Summer Learning for Student Success is a compendium of studies, reports and commentaries by more than 100 thought leaders including community leaders, elected officials, educators, researchers, advocates and other prominent authors that provides examples of effective practices, programs, and partnerships to support positive whole child outcomes.

- Community Schools Playbook provides model legislation, real-world examples, and many additional resources for state and local leaders who want to support community schools.

- What are Community Schools? video describes the four key features of community schools, the importance of community school coordinators, and strategies for funding community schools.

- How to Start a Community School toolkit provides information on how to implement a community school initiative and focuses on several topics, including vision and strategic planning, building a leadership team, needs and capacity assessments, sharing space and facilities, financing your community school, and research and evaluation.

- National Center for Community Schools (NCCS). The focus of NCCS, a part of Children’s Aid, is to build the capacity of schools and districts to work in meaningful long-term relationships with community partners. Since 1994, NCCS has developed a variety of free planning tools, implementation guides, videos, and other resources and has also provided intensive assistance (training, on-site consultation, and strategic planning facilitation) on a fee-for-service basis. NCCS is a founding and active member of the Coalition for Community Schools.

- A School Year Like No Other Demands a New Learning Day: A Blueprint for How Afterschool Programs & Community Partners Can Help offers building blocks for school–community partnerships to address equity and co-construct the learning day in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Afterschool Programs: A Review of Evidence Under the Every Student Succeeds Act (Research for Action). Based on a literature review of studies published since 2000, this review summarizes the effectiveness of specific after-school programs. The review uses the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) evidence framework to assess the evidence of over 60 after-school programs. A companion guide provides profiles of each after-school program included in the review as well as studies of each program’s effectiveness.

- Getting to Work on Summer Learning: Recommended Practices for Success, 2nd Ed. (RAND Corporation). Based on thousands of hours of observations, interviews, and surveys, this report provides guidance for district leaders and their partners for launching, improving, and sustaining effective summer learning programs.

- The Children’s Safety Network (CSN). CSN works with state and jurisdiction Maternal and Child Health programs and Injury and Violence Prevention programs to create an environment in which all infants, children, and youth are safe and healthy.

FOUNDATIONAL SCIENCE OF LEARNING AND DEVELOPMENT RESEARCH

Developmental and learning science tell an optimistic story about what all young people are capable of. There is burgeoning scientific knowledge about the biologic systems that govern human life, including the systems of the human brain. Researchers who are studying the brain’s structure, wiring, and metabolism are documenting the deep extent to which brain growth and life experiences are interdependent and malleable.

Three papers synthesizing this knowledge base form the basis of the design principles for community-based settings presented here. For those seeking access to the research underlying this work, these papers are publicly available.

- Cantor, P., Osher, D., Berg, J., Steyer, L., & Rose, T. (2018). Malleability, plasticity, and individuality: How children learn and develop in context. Applied Developmental Science , 23(4), 307–337. https://doi.org /10.1080/10888691.2017.1398649.

- Darling-Hammond, L., Flook, L., Cook-Harvey, C., Barron, B. J., & Osher, D. (2019). Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development. Applied Developmental Science , 24(2), 97–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2018.1537791.

- Osher, D., Cantor, P., Berg, J., Steyer, L., & Rose, T. (2018). Drivers of human development: How relationships and context shape learning and development. Applied Developmental Science , 24(1), 6–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2017.1398650.

1Finkelhor, D. Turner, H., Ormrod, R., Hamby, S. & Kracke, K. (2009). Children’s exposure to violence: A comprehensive national survey . Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/ojjdp/227744.pdf

2Maier, A., Daniel, J., Oakes, J., & Lam, L. (2017). Community schools as an effective school improvement strategy: A review of the evidence . Learning Policy Institute.

3Neild, R.C., Wilson, S.J., & McClanahan, W. (2019). Afterschool programs: A review of evidence under the Every Student Succeeds Act . Research for Action.

4Acaira, E., Vile, J., & Reisner, E. R. (2010). Citizen Schools: Achieving high school graduation: Citizen Schools’ youth outcomes in Boston . Policy Studies Associates Inc.; Harvard Family Research Base. (n.d.). Out-of-school time evaluation database: A profile of the evaluation of Citizen Schools. https://archive.globalfrp.org/out-of-school-time/ost-database-bibliography/ database/citizen-schools/evaluation-3-2001-2005-phase-iv-findings (accessed 06/24/20).

5Acaira, E., Vile, J., & Reisner, E. R. (2010). Citizen Schools: Achieving high school graduation: Citizen Schools’ youth outcomes in Boston . Policy Studies Associates Inc.; Neild, R. C., Wilson, S. J., & McClanahan, W. (2019). Afterschool evidence guide: A review of evidence under the Every Student Succeeds Act. Research for Action.

6National Commission on Social, Emotional, and Academic Development. (2018). Building partnerships in support of where, when, and how learning happens . Aspen Institute. http://www.aspeninstitute.org/publications/building-partnerships-in- support-of-where-when-how-learning-happens/

7Spielberger, J., Axelrod, J., Dasgupta, D., Cerven, C., Spain, A., Kohm, A., & Mader. N. (2016). Connecting the dots: Data use in afterschool systems . Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago. https://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/ Documents/Connecting-the-Dots-Data-Use-in-Afterschool-Systems.pdf.

8National Commission on Social, Emotional, and Academic Development. (2018). Building partnerships in support of where, when, and how learning happens: Examples and resources from the field . Aspen Institute. https://www.aspeninstitute.org/ wp-content/uploads/2018/10/FINAL-YD-Examples-and-Resources-from-the-Field.pdf

9National Commission on Social, Emotional, and Academic Development. (2018). Building partnerships in support of where, when, and how learning happens: Examples and resources from the field . Aspen Institute. https://www.aspeninstitute.org/ wp-content/uploads/2018/10/FINAL-YD-Examples-and-Resources-from-the-Field.pdf

10Moore, K. A. (2014). Making the grade: Assessing the evidence for integrated student supports . Child Trends. https://www. childtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/2014-07ISSPaper2.pdf.

11Central New York Care Collaborative (CNY Cares) Conducting Warm Handoffs. https://cnycares.org/media/2682/ conducting-warm-handoffs-course-content-rrp-v1.pdf

12Source: Communities in Schools. (n.d.). About us (accessed 3/8/17); Bronstein, L. R., & Mason, S. E. (2016). School-linked services: Promoting equity for children, families and communities . Columbia University Press.

13What are Community Schools? - Partnership for the Future of Learning (futureforlearning.org).

14Oakes, J., Maier, A., & Daniel, J. (2017). Community schools: An evidence-based strategy for equitable school improvement . National Education Policy Center and Learning Policy Institute.

15Moore, K. A., & Emig, C. (2014). Integrated student supports: A summary of the evidence base for policymakers [Whitepaper #2014-05]. Child Trends.

16Oakes, J., Maier, A., & Daniel, J. (2017). Community schools: An evidence-based strategy for equitable school improvement . National Education Policy Center & Learning Policy Institute.

17Johnston, W. R., Engberg, J., Opper, I. M., Sontag-Padilla, L., & Xenakis, L. (2020). Illustrating the promise of community schools: An assessment of the impact of the New York City Community Schools Initiative . RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR3245.html.

18Johnston, W. R., Engberg, J., Opper, I. M., Sontag-Padilla, L., & Xenakis, L. (2020). What is the impact of the New York City Community Schools Initiative? RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB10107.html.