THE POSSIBILITY PROJECT

The Possibility Project, a program for teens age 14-19 in New York, brings together vastly diverse groups of teenagers and uses the performing arts to examine and address the personal and social forces that shape their lives and identities. The program focusses on building community and believe that the relationships that young people develop with each other and with adults is the vehicle of their program’s impact.

In the vignette below, the adults provide intentional structures where young people are able to practice inter- and- intrapersonal skills by sharing their personal stories with each other. They provide opportunities for young people to express care, support and challenge each other, and explore and identify strengths, The adults form positive developmental relationships with young people as they share power with them. They also provide opportunities for youth to lead and decide how to use each other’s stories to create various performing art pieces. Adults take a step back, but continue to provide support, checking in on how youth are feeling, and scaffolding supports for them as needed.

The Possibility Project uses storytelling in a particularly powerful way. The young people in the program first tell their stories to each other, and then ultimately combine their stories and their passions into an original musical performance they present to the community. Young people are not casted for their own story and are intentionally casted in a story that is representing one of their cast member’s stories. There is deep and shared responsibility to tell that story in the best way they can, and the responsibility to not let people down because if they don’t show up for these story-telling sessions, then the whole group can’t build narrative as individual stories are all woven together. Each young person feels the importance of their story and a sense of responsibility to show up for the team, and they reinforce that in each other.

The program facilitates structured time for young people to build relationships with each other and understand where they are coming from to truly represent each other’s stories in an authentic way. They have one-on-ones: between pairs of participants (A and B) in which A asks a question of his/her partner B. When B is done answering, B asks a question of A. At the end, everyone scrambles and switches partners for a second round of one-on- ones. Participants, both adults and young people, are instructed to ask questions from a place of curiosity about the person across from them. Young people from the program share that they feel genuine care from the adults because of how they check in with them. They mentioned that the adults remember conversations they had with them and inquire about past events. A youth shares, “they remember what you’re going through and it’s just like, ‘Hey, how’s that going? Do you need to talk, because I’m still here for you?’ It’s not like, ‘Oh, you need someone.’ Or, ‘I’m listening to you,’ and then like a week later they’ll never talk about that again. They’re still there. They’re still checking in. ”

Along the way, the young people develop self-awareness as well as acting and singing skills. The staff gradually let young people take over more of the decision-making and artistic control as they design and rehearse for their final performance to the community.

Source: Adapted from Smith, Charles, Gina McGovern, Reed Larson, Barbara Hillaker, and Stephen C. Peck. (2016) Preparing youth to thrive: Promising practices for social and emotional learning . Forum for Youth Investment.

WHAT ARE POSITIVE DEVELOPMENTAL RELATIONSHIPS?

Positive developmental relationships enable everyone to manage stress, ignite their brains, and fuel the connections that support the development of the complex skills and competencies necessary for learning success and engagement. Such relationships also simultaneously promote well-being, positive identity development, and a young person’s belief in their own abilities.

Caregivers, parents, and other family members from all backgrounds want their children, at any age, to be in settings where they are well known, cared for, respected, and empowered to learn. All caregivers hope that their children will be able to feel safe and valued wherever they are spending their time, and all children deserve such contexts for learning and development. Recent brain research affirms that secure relationships build healthy brains that are necessary for development and learning.

Having secure relationships does not just mean that young people are treated kindly by adults. It also means that young people are nurtured and respected through those relationships to develop independence, competency, and agency—that they grow to become confident and self- directed learners and people.

Developmental relationships provide the avenue to learning and growth and buffer individuals’ negative experiences and stress. A strong web of relationships between and among children and youth, peers, families, and educators, both in the school and in the community, represent a primary process through which all members of the community can thrive.

WHY ARE DEVELOPMENTAL RELATIONSHIPS IMPORTANT?

WHAT THE SCIENCE SAYS

Relationships that are reciprocal, attuned, culturally responsive, and trustful are a positive developmental force in the lives of all young people. For example, when an infant reaches out for interaction through eye contact, babble, or gesture, a parent’s ability to accurately interpret and respond to their baby’s cues affects the wiring of brain circuits that support skill development.

These reciprocal and dynamic interactions literally shape the architecture of the developing brain and support the integration of social, affective, and cognitive circuits and processes, not only in infancy but throughout the school years and beyond. When children and youth interact positively with practitioners and peers, qualitative changes occur in their developing brains that establish pathways for lifelong learning and adaptation.

Research has found that a stable relationship with at least one committed adult can buffer the potentially negative effects of even serious adversity.

These relationships, which provide emotional security and reduce anxiety, are characterized by consistency, empathetic communications, modeling of productive social behaviors, and the ability to accurately perceive and respond to a child’s needs. Search Institute’s studies on developmental relationships indicate that young people who experience strong developmental relationships: are more likely to report a wide range of social-emotional strengths and other indicators of well- being and thriving; are more resilient in the face of stress and trauma; and do better when they experience a strong web of relationships with many people1.

WHAT CAN COMMUNITY-BASED LEARNING AND DEVELOPMENT SETTINGS DO TO FOSTER POSITIVE DEVELOPMENTAL RELATIONSHIPS?

Most young people report that the parenting adults in their lives are the strongest source of developmental relationships—not surprisingly, as families provide the foundation of care from birth onward and get know their children best. Search Institute administered the SPARK Youth Voice Survey to over 3000 adolescents in grades six through 12 in a large, diverse U.S. city and found that parenting adults most often exhibited the elements of developmental relationships, while community program leaders and teachers were about equally as likely to build developmental relationships with young people.3

While families are the most common sources of developmental relationships that provide the foundation for young people’s success, developmental relationships need to extend beyond family members to include the many other adults in the community with whom youth interact—youth practitioners to mentors, to museum docents, to coaches. When all adults work to support positive developmental relationships, webs of support are created that recognize that youth are active agents in relationships, their relationships are embedded within a broader ecology of relationships (and other supports), and different adults will provide different sets of social supports.4

There are three ways that community-based learning and development settings support developmental relationships with young people. First and foremost, the adults in community-based settings form developmental relationships with young people in their settings. Secondly, they cultivate relationships with family members. Working together with family members can build on or even improve the relationships family members already have with young people and improve the capacity of staff to support young people’s development. Lastly, when programs foster relationships among young people by providing opportunities to mentor and lead , older youth can form developmental relationships with peers and younger program participants in ways that inspire and encourage the younger ones.

How to Build Positive Developmental Relationships

-

Foster developmental relationships between adults and youth

- Cultivate relationships with family members

- Foster relationships among young people by providing opportunities to lead and mentor

Foster Developmental Relationships Between Adults and Young People

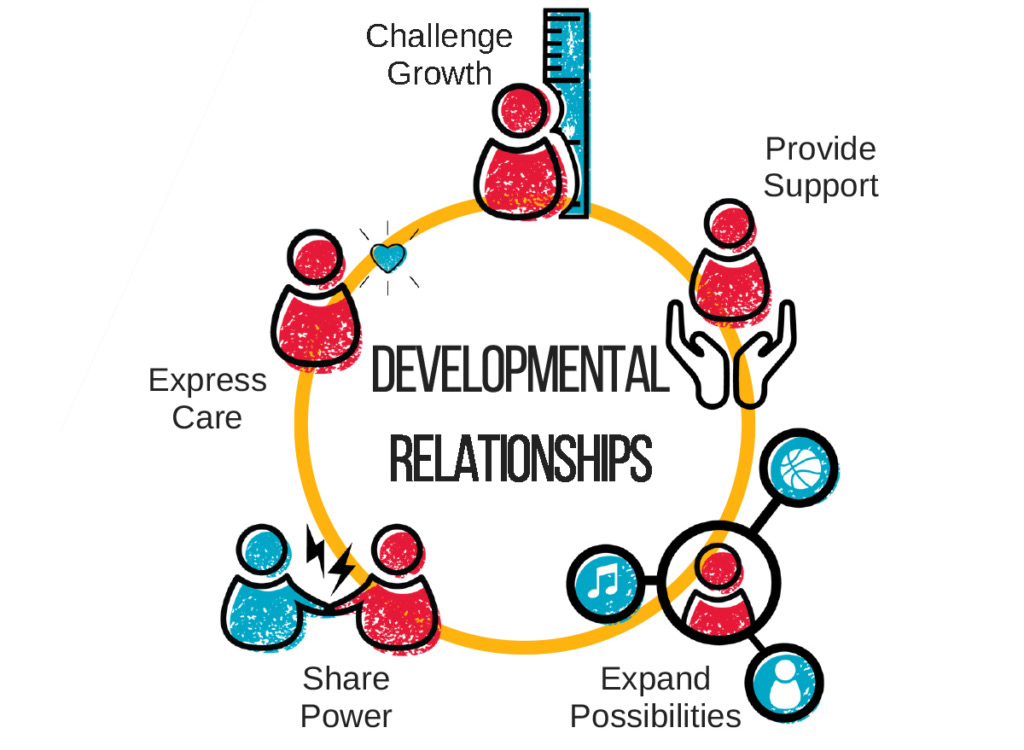

The Search Institute describes five ways adults create developmental relationships with young people: express care; challenge growth; provide support; share power; and expand possibilities.5 These five elements help young people:

- Discover who they are

- Develop abilities to shape their own lives

- Learn how to engage with and contribute to the world around them6

Key Practices to Form Developmental Relationships Between Adults and Young People

Together, the five elements of developmental relationships when implemented in community-based settings, lead to three main practices.

For a relationship with a young person to promote positive development it must foundationally be warm, dependable, and encouraging. Being aware of young people as individuals, greeting them by name, and welcoming warmly them and treating them with respect is foundational. Using responsive practices helps foster developmental relationships between adults and young people. Responsive practices are ones in which staff respond to young people based on their unique needs, experiences and strengths, particularly when adults respond or adjust in the moment, based on shared conversation about what is best for the young person at that moment. Responsive practices include:

- Observing and interacting in order to know youth deeply

- Providing structure for check-ins to actively listen to and receive feedback from individual youth

- Coaching, modeling, scaffolding, and facilitating in real time as challenges occurs

Incorporating responsive practices into community- based settings involves incorporating appropriate structures like get-to-know-you activities and the check-ins mentioned above. Having young people tell their stories is a powerful structure for getting to know the young people deeply. Young people learn more about themselves as they learn about others. Regular structured opportunities for sharing and reflection are practices that a variety of community-based learning and development opportunities can implement.

Sharing control or power with young people involves giving young people choices and supporting autonomy, independence, and decision-making as their skills and competence grow. The adult role is to guide and facilitate as needed. Practical strategies for sharing controls with young people include: encouraging young people to give feedback, providing input on decisions that affect them, and generating ideas.

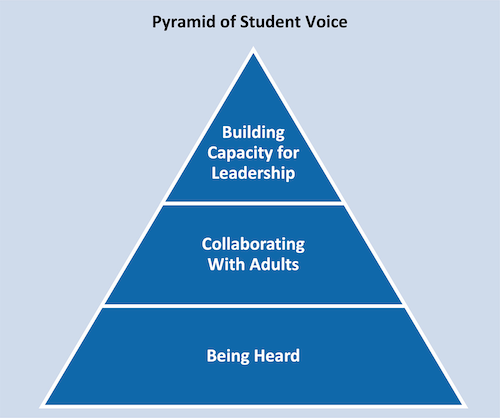

The Pyramid of Student Voice7 provides a framework for thinking about how young people can move toward increased autonomy and decision-making. The pyramid begins at the bottom with the most common and most basic form of youth voice—’being heard.’ At this level, adults listen to young people to learn about their experiences in the learning and development setting. ‘Collaborating with adults’ is the next level. It describes instances in which young people work with adults to make changes in the school, including collecting data on problems and implementing solutions. The final level at the top of the pyramid, ‘Building capacity for leadership,’ includes an explicit focus on enabling young people to share in the leadership of the youth voice initiative.

In the Strive Forward program, at Minnesota’s Voyageur Outward Bound School , staff increasingly share power with the young people as their outdoor skills grow. The program is intentionally sequenced to build a progression using three phases to create a graduated level of responsibility for youth. The three phases—Training (Learning) Phase, Main (Leadership) Phase, and Final (Responsibility) Phase—are stretched out over the year, with youth spending roughly three months in each phase, but progressing through them at their own pace.

In the beginning the staff structure everything, providing lots of training and hands-on help. As the practical and leadership skills grow for the youth, ages 14 to 18, the staff step back and transfer responsibility to the youth who set goals, make decisions, and take the lead in their expeditions.

Developmental relationships empower and inspire young people, enabling them to discover and develop their strengths, build their confidence, and take on challenges. Many community- based settings provide structures for young people to learn about themselves in ways that the academic priorities do not allow time for in the classroom. In many cases, young people or their care-taking adults can select environments that are conducive for developing and displaying the strengths, interests, and talents of young people that may not emerge in an academic setting, affording youth opportunities to explore interest areas without concern about grades.

Some settings focus on developing a particular skill or interest area such as a basketball, chess, or music, while some provide a wide range of choices and interest areas within one program. Many others provide leadership opportunities or opportunities for civic engagement. Adults in community-based learning and development opportunities can help young people see possibilities within their community, but also expand their range of experiences beyond their community. In community- based learning and development opportunities such as camps, museums, and art venues, adults have unique opportunities to show young people an expanded set of possibilities for their lives and encourage them to explore and develop new interests and talents.

Whatever the context, adults interacting with young people need to be able to describe and name individuals’ strengths, express confidence in the young person and encourage the young person to believe in themselves. This requires that practitioners commit to an unconditional positive regard for the young people in the program.

Cultivate Relationships with Family Members

The research is clear that families are most often the source of developmental relationships with young people, therefore, when other adults who work with young people partner with families it supports developmental relationships with young people.

Key Practices to Cultivate Relationships with Family Members

Practices that support positive relationships with family members begin with seeing families through a strength- based lens. Adults who work with young people often say family engagement or family involvement is important. At the same time, families may be viewed from a deficit lens. Behavior problems may be viewed as the fault of family upbringing and the strengths of family culture may not be recognized. While the possibility of abuse or neglect within a family cannot be overlooked, recognizing family strengths and assuming families want the best for their children is always the place to start.

The Michigan Hispanic Collaborative is a non-profit organization that provides academic and career support programs to enable more Hispanic students to graduate from college and achieve career success. They follow a two-generation approach to engage both families and young people in the learning process. They use a cafecitos (Café) model where they bring young people and families together to build a strong and supportive community.

Parents benefit as they get practical advice from an experienced parent peer facilitator, a Hispanic professional, and other families to understand the academic process. It aims to empower both families and young people to support successful learning.

Research links family involvement with improved learning and outcomes for young people.8 Sometimes family involvement in community-based settings is more accessible than involvement in school. Programs and activities are more likely to be scheduled for afterschool, evenings, and weekends, so family members may have more routine connection points to community learning and development opportunities than to school settings. They may drop off or pick up their children and youth, they may watch sports games or other performances, or they may volunteer or provide snacks. If community programs are staffed by volunteers from the community the young people live in, family members may already know the leaders, and may share cultural or ethnic backgrounds with them. Additionally, community learning and development opportunities are more likely to have relationships with young people that endure over a period of years, enhancing opportunities to get to know young people and family members well. In some cases, adults may be closer to the young person’s age and may be an example of achievement that young people can relate to.

Family engagement starts with clear and welcoming communications and established mechanisms (e.g., newsletters, email, conferences, group meetings, dinners, picnics) to keep family members and other caregivers informed as well as to ask for suggestions and feedback. It also requires that adults share with parents or guardian examples of their children and youth’s achievements, progress, and positive behavior either in person or through various technology platforms.

It is important to ensure that interactions with family members are not just about negative behaviors or performance. Central to effective family engagement efforts are inclusion and accessibility, with logistical barriers to engagement, such as translation, removed.

Showing up at events for their children and youth may be viewed as families’ primary form of involvement or contribution to young people’s learning. However, families and guardians support young people’s learning in many ways—from reading to their children, to helping with homework. In the middle school years, however, a meta-analysis found parents’ academic socialization to be a better predictor of achievement than direct involvement.9 Academic socialization includes having high expectations for their children and youth, valuing education, and helping them prepare and plan for the future. Practitioners in community-based settings can support and supplement families’ and guardians’ role in academic socialization, as adults can also convey high expectations and possibilities for young people.

Practices that support partnerships with family members begin with seeing families through a strength-based lens. Building on that involves creating structures for adults in community-based learning and development opportunities and families to learn from each other and work together in the best interests of the young person. Families advocate for their children and youth. Family members and guardians can share insights into their young person’s personality, interests, culture, and behavior, thus helping adults be more responsive to the young people in their program. Adults in community- based settings can share successes and achievements of the young person in their program, providing an additional opportunity for family members to express pride in their young person. Adults can work with family members to strategize how to support young people in improving their skills and engaging successfully in learning settings. They may model supportive language and provide resources on child or adolescent development. And, of course, one of the primary ways’ families expand possibilities for their children and youth is by connecting them to community-based learning and development settings.

The Dual Capacity-Building Framework (Figure 9), while developed to help schools and districts improve their partnerships with families, is equally applicable to community-based settings. It articulates the essential conditions for effective partnerships with families—i.e., the partnership is collaborative, interactive, culturally responsive and respectful, asset based, built on mutual trust, and linked to learning and development, coupled with essential organization conditions including system level leadership buy in, integrated and embedded in all strategies and sustained by resources and infrastructure support. With these process and organizational conditions in place, both practitioners and families are able to build and enhance their capacity to develop capabilities, make connections, connections, increase cognition, and improve confidence. Together, these capacities empower both practitioners and families to connect their partnership to learning and development, become co-creators, honor the assets they bring, and advocate on behalf of the young people.

Foster Relationships Among Young People by Providing Opportunities to Mentor and Lead

Another source of developmental relationships for young people can be older youth. Some community- based settings have traditions or practices that provide older youth with an opportunity to lead or mentor those younger or less experienced. Sometimes these are even paid opportunities. Camp programs sometimes use older, experienced campers to provide leadership and support to younger campers using models such as Counselors in Training (CIT). Sports programs and other community- based learning and development opportunities may also look for older youth to work with younger youth, providing valuable assistance to the program leaders, opportunities for growth in leadership for the older youth, and someone closer to their own age to be a role model and example for the younger ones. Having someone to look up to that comes from a similar background makes identification with a role model easier, whether that person is an older youth or an adult leader.

Key Practices to Foster Relationships Among Young People by Providing Opportunities to Mentor and Lead

Young people, especially teens, are capable of significant leadership and responsibility, but they need support and training. Sometimes this support can be informal—a staff member taking a young person under their wing—but intentionally structuring a program so that staff members both encourage and coach and provide training is important. Some community-based learning and development opportunities invite older participants to serve as mentors or assistant leaders for younger participants and create training specifically for them.

Camps refer to these older campers as CITs. Other types of programs provide various types of leadership opportunities, but to maximize the benefit for participants of all ages, it is best to intentionally utilize and encourage developmental relationships.

The YMCA Storer Camps provide two-week training and service experience for older youth who desire to grow as leaders and potentially prepare themselves to be full camp counselors in the future. Young people must submit an application to participate in the program. The CITs live side-by-side with camp counselors, take workshops where they learn behavior management, age characteristics and other topics, engage in team building and are supported to exercise leadership in their cabins. CITs also develop relationships with younger campers. Since CITs are an integral part of the camp experience, younger campers can see the CITs as role models and know they could one day be a CIT.

Young people often more easily identify with another young person than with an adult leader. It is easier to envision themselves in a few years, recognizing how continued involvement in the community-based learning and development opportunities can lead to successful skill development and leadership opportunities. Programs that intentionally utilize older youth as assistants or even have an established training path for youth leadership, make it clear that leadership is a possibility for young people. Young people can see that they need not outgrow participation in the program but have a level of challenge and responsibility they can grow into.

Each year, The Possibility Project —the program described at the beginning of this chapter—establishes a Production Team comprised of six-ten returning cast members and two new cast members. This Production Team gets to know new cast members, helping them to feel safe and supported. As new cast members see Production Team members exercise significant leadership over setting goals, planning, hiring, and solving problems, new cast members realize that it is also possible for them to grow from novice to leader.

SUMMARY

Developmental relationships depend on mutual respect, knowing a person well, expressing care and support, seeing their strengths, and creating an environment that brings out the best in young people. Adults in community-based learning and development opportunities have specific assets when it comes to being a source of developmental relationships for youth and children. Adults who work and volunteer in community-based settings may have greater ties to home, family, and culture as they often come from within the community may have a head start in building trusting relationships with young people. If program leaders are from the community of the young people, they can intuitively identify and affirm young people’s cultural strengths and build trust. Community-based settings with mixed age-groups that continue to meet year after year have a unique opportunity to encourage developmental relationships between older and younger youth. Ideally, families help adults in community-based learning and development opportunities to know their young people better, supporting developmental relationships between adults and young people and may provide resources to families to support developmental relationships in the family.

Families support the development of their children and youth when they enroll them in community-based learning and development settings. These settings can expand young people’s horizons beyond their community or comfort area. Museums and libraries may figuratively take young people outside of their home communities, exposing them to new worlds. Camp or residential settings may literally take young people beyond the community, immersing them in a challenging and supportive program where deep relationships can be formed and young people can be introduced to novel experiences and new environments. Even within their home community, young people may be encouraged to see themselves in new ways through civic engagement or leadership opportunities. These opportunities, combined with trusted, caring relationships with adults and others, are key to young people thriving and learning. The following section lists some resources programs may use to learn about or support developmental relationships.

TOOLS AND RESOURCES TO CREATE POSITIVE DEVELOPMENTAL RELATIONSHIPS

- Preparing Youth and Children to Thrive are two field guides that provide cases studies of exemplary community-based learning and development opportunities and how they create structures and opportunities that build caring and meaningful relationships with young people that challenge, support and expand possibilities.

- The Search Institute has many resources on developmental relationships for families, schools, programs and organizations. Keep Connected is a curriculum based on developmental relationships for young people and their families that schools and community or faith-based organizations can sponsor. They also have resources for how families can spend time together and make an intentional space to develop relationships.

- The Afterschool Guide to Building Relationships and Routines E book helps afterschool professionals create safe, supportive environment based on program activities that build relationships and routines and are based on the Science of Learning and Development.

- Playworks provides various resources across age groups and group sizes for both in-person and virtual settings that help to build relationships, build adult-youth relationships, and solve conflicts.

- Family Engagement in Anywhere, Anytime Learning guide encourages youth development workers and community programs to support families in providing developmental relationships with their children that expand the interests and, possibilities. It provides links to resources for how community-based learning and development opportunities and families can work together to support young people.

- The Dual Capacity Building Framework for Family-School Partnerships was formulated using the research on effective family engagement and home–school partnership strategies and practices, adult learning and motivation, and leadership development. While aimed at school-family partnerships the framework is equally applicable to community learning and development opportunities.

- Navigating Your Way to Success. This online course provides a curriculum for afterschool programs to use with families and their children who are in or approaching the middle school years. Through the courses, participants will receive a set of six themed program sessions with activities for young people and their families to engage in together with afterschool staff.

- AMP’s Top Ten Tips for Engaging with Young People is a simple and practical guide for engaging in a supportive conversation with young people. It includes examples of what types of things to say and what not to say.

- Peer Mentoring: A Discussion with Experienced Practitioners webinar engages mentoring practitioners around best practices for engaging young people to become mentors to other young people.

- The Mentor’s Guide to Youth Purpose. Mentors have a unique opportunity to help youth find meaning, a sense of self, and ways of giving back to their world. MENTOR’s resource is a how-to guide for mentors and the young people in their lives. The Mentor’s Guide to Youth Purpose includes directive tips and worksheets to help adults and young people understand and explore purpose together.

FOUNDATIONAL SCIENCE OF LEARNING AND DEVELOPMENT RESEARCH

Developmental and learning science tell an optimistic story about what all young people are capable of. There is burgeoning scientific knowledge about the biologic systems that govern human life, including the systems of the human brain. Researchers who are studying the brain’s structure, wiring, and metabolism are documenting the deep extent to which brain growth and life experiences are interdependent and malleable.

Three papers synthesizing this knowledge base form the basis of the design principles for community-based settings presented here. For those seeking access to the research underlying this work, these papers are publicly available.

- Cantor, P., Osher, D., Berg, J., Steyer, L., & Rose, T. (2018). Malleability, plasticity, and individuality: How children learn and develop in context. Applied Developmental Science , 23(4), 307–337. https://doi.org /10.1080/10888691.2017.1398649.

- Darling-Hammond, L., Flook, L., Cook-Harvey, C., Barron, B. J., & Osher, D. (2019). Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development. Applied Developmental Science , 24(2), 97–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2018.1537791.

- Osher, D., Cantor, P., Berg, J., Steyer, L., & Rose, T. (2018). Drivers of human development: How relationships and context shape learning and development. Applied Developmental Science , 24(1), 6–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2017.1398650.

1Roehlkepartain, E. C., Pekel, K., Syvertsen, A., Sethi, J., Sullivan, T. K., & Scales, P. C. (2017). Relationships first: Creating connections that help young people thrive . The Search Institute.

2Roehlkepartain, et.al. (2017).

3SPARK and Search Institute. (2019). HELPING KIDS THRIVE AT HOME: How Itasca area youth experience strength and resilience in their relationships with parents and grandparents . The Search Institute. https://www.search-institute.org/wp- content/uploads/2019/07/2018_SPARK_Report_Families_final.pdf

4S. M., & Zaff, J. F. (2017). Defining Webs of Support. https://www.americaspromise.org/resource/defining-webs-support- new-framework-advance-understanding-relationships-and-youth

5Roehlkepartain, et.al. (2017).

6Roehlkepartain, et.al. (2017).

7Mitra, D. (2006). Increasing student voice and moving toward youth leadership. The Prevention Researcher , 13(1), 7-10.

8Jeynes, W.H. (2013). “A meta-analysis of the efficacy of different types of parental involvement programs for urban students.” FINE Newsletter, V(1). https://archive.globalfrp.org/family-involvement/publications-resources/a-meta-analysis-of-the- efficacy-of-different-types-of-parental-involvement-programs-for-urban-students ; Dearing, E., Kreider, H., Simpkins, S., & Weiss, H. B. (2006). Family involvement in school and low-income children’s literacy: Longitudinal associations between and within families. Journal of Educational Psychology , 98(4), 653-664.

9Hill, N. E., & Tyson, D. F. (2009). Parental involvement in middle school: a meta-analytic assessment of the strategies that promote achievement. Developmental Psychology , 45(3), 740-763.

10Borah, P., Conn, M., Pittman, K. (2019). Preparing children to thrive: Standards for social and emotional learning practices in school-age settings . The David P. Weikart Center for Youth Program Quality.