OVERVIEW OF THE GUIDING PRINCIPLES FOR EQUITABLE WHOLE CHILD DESIGN*

*Adapted from Design Principles for Schools: Putting the Science of Learning and Development Into Action, 2021

Emerging science tells an optimistic story about the potential of all learners. There is burgeoning knowledge about the biological systems that govern development, including deeper understandings of brain structure and wiring and its connections to other systems and the external world. This research indicates that brain development and life experiences are interdependent and malleable—that is, the settings and conditions individuals are exposed to and immersed in affect how they grow throughout their lives.

With this knowledge about the brain and development, coupled with a growing knowledge base from multi- disciplinary research, there is an opportunity to design learning systems in which all individuals are able to take advantage of high-quality opportunities for transformative learning and development. The situation facing our country today—sharp and growing economic inequality, ongoing racial violence, the physical and psychological toll of the pandemic—underscores the need to enable societal and educational transformations that advance social justice and the opportunity to thrive for each and every young person.

THE GUIDING PRINCIPLES FOR EQUITABLE WHOLE CHILD DESIGN

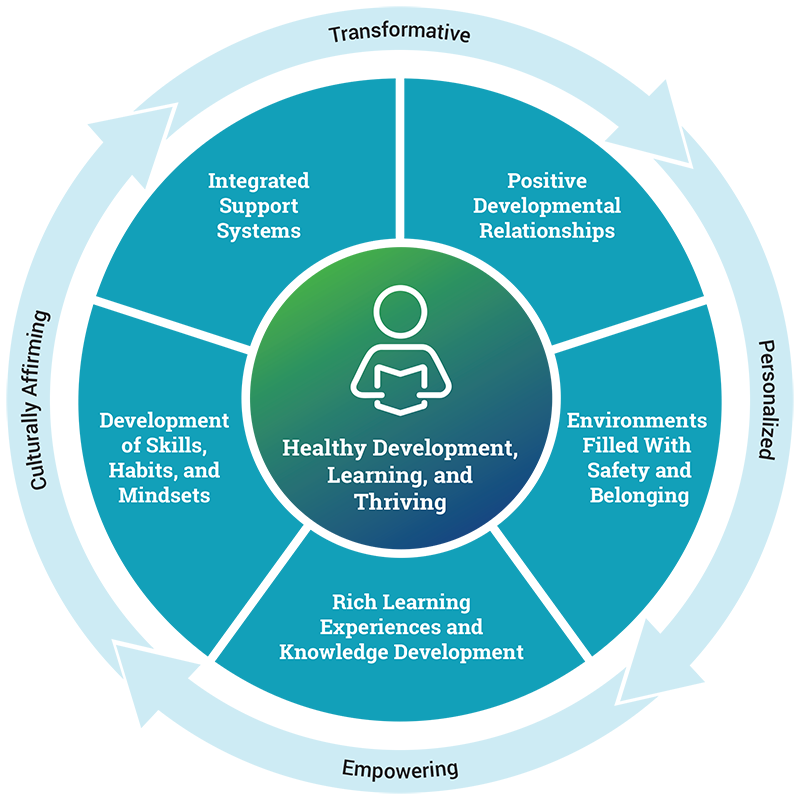

The Guiding Principles for Equitable Whole Child Design aim to seize this opportunity to advance change. The organizing framework to guide transformation of learning settings for children and adolescents is depicted in Figure 1. The inner circle names the five science-based elements that, taken together, are the guiding principles for healthy development, learning, and thriving:

- Positive Developmental Relationships

- Environments Filled with Safety and Belonging

- Rich Learning Experiences and Knowledge Development

- Development of Skills, Habits, and Mindsets

- Integrated Support Systems

The outer circle of the graphic names the four essential conditions for equitable whole child design: all learning and development settings need to be transformative, personalized, empowering, and culturally affirming. In day-to-day practice, all of these elements need to be considered and actualized together.

The five elements in many ways are not controversial and resonate with many community-based practitioners already. However, they have not yet been widely used to develop and create learning settings, nor have they been engineered in fully integrated ways to yield healthy development, learning, and thriving. Progress has been impeded by both historical traditions and current policy built on dated assumptions about learning environments, accountability, assessment and practitioner development. Current constraints do not support robust implementation, let alone integration of these practices. If, however, the purpose of education is the equitable, holistic development of each young person, scientific knowledge from diverse fields can be used to redesign policies and practices to create settings across the learning and development ecosystem that unleash the potential of each and every learner.

The guiding principles do not to suggest a single answer or check list; the desired result is increasingly robust innovations and new collaborations aligned with the resources for positive growth found in young people’s communities and cultures. Redesign around these core principles should influence all levels of the ecosystem from the classroom to the school, to the district and the larger macrosystems (e.g., teacher preparation and higher ed). But it should go further to influence the myriad of community-based learning and development settings that will join together to produce an intentionally integrated, comprehensive developmental enterprise committed to equity for all learners, not just some learners. Each component is separated and enumerated individually, but the unique application of these components will be to build them in reinforcing and integrated ways to truly support learner needs, interests, talents, voice, and agency. The aim is a context for development that is greater than the sum of its parts and is transformative, personalized, empowering, and culturally affirming for each and every learner.

The framework, described below, defines and names how each of the elements of whole child design is associated with key principles from developmental and learning science and from excellent youth development practice. The design principles playbooks are not how-to manuals or easy checklists, but rather a way to think about describing, assessing, and co-designing new learning and development ecosystems in partnership with youth, educators, families, and community-based practitioners.

That relationships are important is not new knowledge to practitioners, families, or researchers. Relationships engage children and youth in ways that help them define who they are, what they can become and how and why they are important to other people. However, not all relationships are developmentally supportive. The key characteristics of a developmental relationship include emotional caring and attachment, reciprocity, progressive complexity, and a balance of power. The emotional connection is joined with adult guidance that enables young people to learn skills, grow in their competence and confidence, become more able to perform tasks on their own and take on new challenges. Children and youth increasingly use their own agency to develop their curiosity and capacities for self-direction. Looked at this way, developmental relationships can both buffer the impact of stress and provide a pathway to motivation, self-efficacy, learning, and further growth.

A strong web of relationships between and among young people and their peers, families, and practitioners, both in the school and in the community, represents a primary process through which all members of the community can thrive. Community-based settings can be organized to foster positive developmental relationships through structures and practices that allow for effective caring and the building of community.

There are three primary ways that community-based learning and development settings can and do support developmental relationships with young people.

- First, adults in community settings form developmental relationships with young people in their settings. This includes: providing responsive support and caring; sharing leadership with young people; and using strategies to help young people discover their strengths, expand their possibilities, and challenge growth.

- Adults cultivate relationships with family members. Working together with family members can build on or even improve the relationships family members already have with young people and improve the capacity of staff to support young people’s development. Specific ways community-based settings cultivate relationships with family members include: seeing families through a strength-based lens; providing opportunities for family engagement; and fostering mutual learning and decision-making.

- Another source of developmental relationships for young people can be older youth. While having positive relationships among peers is important in all community-based learning and development settings, some settings go beyond just supporting positive relationships among the young to providing opportunities for developmental relationships among young people. They have traditions or practices that provide older youth with an opportunity to lead or mentor those younger or less experienced youth.

The community-based settings or contexts of development, such as afterschool and summer programs, sports programs, and museums and libraries, drive the development of who we become, including the expression of our genes. This is especially important as the cues from our social and physical world determine which of our 20,000 genes will be expressed and when. Over our lifetimes, fewer than ten percent of our genes actually get expressed. This biological process highlights the malleability and plasticity of development that is both an opportunity and vulnerability. When settings are designed in ways that support connection, safety and agency, a positive context is created.

The brain is a prediction machine that loves order; it is calm when things are orderly and gets unsettled when it does not know what is coming next. Learning communities that have shared values, routines, and high expectations—that demonstrate cultural sensitivity and communicate worth—create calm and ignite the other part of the brain that loves novelty and is curious. Children are more able to learn and take risks when they feel not only physically safe with consistent routines and order, but also emotionally and identity safe, where they and their culture are a valued part of the community they are in.

In contrast, anxiety and toxic stress are created by negative stereotypes and biases, bullying or microaggressions, unfair discipline practices, and other exclusionary or shaming practices. These are impediments to learning because they preoccupy the brain with worry and fear. Instead, co-creating norms; enabling young people to take agency in their learning and contribute to the community; and having predictable, fair, and consistent routines and expectations for all community members create a strong sense of belonging.

There are three primary ways that community-based learning and development settings can and do foster environments filled with safety and belonging:

- First and foremost, these learning and development settings need to feel like safe spaces for young people, with consistent routines and expectations. This means creating consistent rituals and routines; helping young people build personal connections and a sense of purpose; and using restorative practices to help young people to reflect on any mistake, solve conflicts, and get counseling when needed.

- A key strategy for helping young people feel like they belong is to intentionally create a sense of community among peers and adults. Doing so involves using positive behavior management practices aimed at fostering a healthy, inclusive community; fostering strong peer to peer relationships; and co-developing program expectations with young people.

- Finally, environments that promote belonging feel inclusive of and culturally responsive to all participants. This means that adults need to: use affirmations that establish the value of every young person’s many identities and abilities and actively counter stereotypes and bias; build on the diversity and cultural knowledge of young people and their families to make learning engaging; and develop young people’s knowledge, skills, and agency to critically engage in civic affairs.

Rich learning experiences require that adults provide both meaningful and challenging work, within and across core disciplines (including the arts, music, and physical education) for all learners, that build on learners’ culture, prior knowledge and experience, and help them discover what they can do and are capable of in their zone of proximal development.3 Young people learn best when they are engaged in authentic activities and are collaboratively working and learning with peers to deepen their understanding and transfer of skills to different contexts and new problems.

Learning is highly variable, and each learner will have their own pathways of learning and their own areas of significant talent and interest. They will be empowered along these pathways through formal and informal feedback, from peers and adults as they engage in activities. The acquisition of more complex and deeper learning skills will be prioritized and personalized for each child, recognizing that learning will happen in fits and starts which require flexible scaffolding and supports along with methods to leverage learners’ strengths to address areas for growth, while differentiating strategies to reach these goals.

There are three primary ways that community-based programs can and do use science findings to create rich learning experiences.

- First, they use scaffolding and differentiation techniques to support each young person’s individual learning style. These techniques include: assessing and adjusting programming to fit the interests, strengths, and needs of young people; providing asset based personalized supports to encourage all young people to persevere and improve; and managing groupwork to support cooperative learning.

- Creating rich learning experiences means that practitioners use inquiry-based approaches to learning that help youth be active and engaged learners. Community-based programs, because of their voluntary nature, provide young people with a wide range of choices and thereby are well- poised to let young people take charge of what questions or problems they are curious about and want to investigate and analyze. Practitioners can support them by asking effective questions that enable them to problem solve, think through various considerations of possibilities and alternatives, and apply that knowledge in various settings.

- Rich learning experiences occur in culturally responsive learning environments that celebrate the unique identities of all learners, while building on their diverse experiences to support rich and inclusive learning.4 This asset-based orientation rejects the idea that practitioners should be colorblind or ignore cultural differences, as these orientations can have harmful effects on learning and development. Instead, culturally responsive practitioners place young people at the center by inviting their multifaceted identities and backgrounds into the learning setting to inform content, instruction, and learning structures.5

The science tells us that learning is integrated—there is not a math part of the brain that is separate from the self-regulation or social skills part of the brain.6 This means parts of the brain are cross-wired and functionally interconnected. For young people to become engaged, effective learners, adult practitioners need to simultaneously develop content specific knowledge and skills along with cognitive, emotional, and social skills. This way of learning needs to be incentivized by systems and leaders, planned for, explicitly taught, and integrated across curriculum areas and across all learning settings.7 These skills, including executive functions, growth mindset, social awareness, resilience and perseverance, metacognition, curiosity, self-direction, and civic engagement are malleable skills and need to be taught, modeled, and practiced just like traditional academic skills.

Supporting young people’s learning and development means supporting them in developing the capacities—the skills, habits, and mindsets—to direct and engage in their own learning. These capacities include understanding of and growth in social and emotional learning (SEL) skills, habits of mind for learning and persevering in learning, and sufficient health and wholeness to engage in the learning process.

Helping young people develop these capacities means that community-based learning and development settings implement practices that:

- Integrate social and emotional learning in a culturally responsive context by: fostering awareness and understanding of young people’s emotions and support meta-cognitive thinking processes; promoting young people’s self- regulation by actively providing them with strategies that support them to both express and manage emotions; and ensuring cultural sensitivity and responsiveness.

- Help young people develop productive mindsets and habits through: nurturing young people’s growth mindset by using growth- oriented language and practice; providing opportunities for planning and goal setting; and supporting interpersonal skills like empathy, collaboration and problem solving.

- Create an environment that incorporates healing-centered practices by: employing responsive strategies that are based on the principles of safety, trust, collaboration, choice, and empowerment; and promoting physical and mental well-being through mindfulness strategies, breathing exercises, and other stress relieving practices.

All young people need support and opportunity.

And all learners have unique needs, interests, and assets to build upon, as well as areas of vulnerability to strengthen without stigma or shame. Therefore, learning environments need to be set up with many protective factors, including health, mental health, and social service supports as well as a universal focus on relationships, supportive environments and skill building. Building both comprehensive and integrated supports will tip the balance toward a learning and development ecosystem where young people feel safe, ready, and engaged.

A well designed and implemented support system weaves together school and community resources to enhance equity of opportunity for success throughout the learning and development ecosystem and it recognizes the value of partnerships across settings. Community- based partners can and do provide assistance vital to social and academic success in classrooms and schools and connect learners and their families to services that promote holistic development. But they also work with other community-based partners and child and youth systems to make sure that all young people are connected to the supports they need to succeed.

Community-based learning and development settings can and do contribute to integrated support systems in two primary ways:

- Help children and youth access supplemental learning opportunities that contribute to academic growth by: partnering with schools to provide seamless and aligned supports for youth; monitoring youth’s academic progress and growth; and adding adult capacity to the school day to support learning.

- Promote access to other supports and opportunities that foster health and well- being by: ensuring mechanisms and partnerships are in place to connect families and youth to basic needs such as food, health, and mental health in addition to academic supports; and participating in whole-school comprehensive community partnership models.

THE POWER OF INTEGRATING PRACTICES

Developmental and learning science provides us with optimism about what all young people are capable of. The contexts and relationships they are exposed to influence what they learn and who they become. Today, we can use the Guiding Principles for Equitable Whole Child Design and its associated design principles to build environments in all of our classrooms, schools, and community-based learning settings that enable all young people to develop and thrive. By designing all learning settings that integrate the five elements—Positive Developmental Relationships; Environments Filled With Safety and Belonging; Rich Learning Experiences and Knowledge Development; Development of Skills, Habits, and Mindsets; and Integrated Support Systems—we can help youth build resilience and knowledge; develop their full selves; and grow skills, habits, and mindsets they need to live lives of fulfillment.

While the Guiding Principles for Equitable Whole Child Design are each critical to supporting youth learning and development, their impact is deeply felt and effective when practitioners integrate all five into a coherent, continuously reinforcing set of practices that aim to be transformative, personalized, empowering, and culturally affirming. Once we understand that environments, experiences, and relationships drive the wiring of our brains, the task and responsibility before us becomes clear: to design settings and experiences for optimal development and learning. This is the purpose and the foundation for the Guiding Principles for Equitable Whole Child Design presented in this playbook. The development of a whole child emerges when we combine the five elements into experiences that connect to one another.

CONCLUSION

The framework for the design principles is built on a theoretical foundation of how children learn and develop that is inherently optimistic and recognizes the power of educators, families, youth practitioners, and other practitioners from diverse disciplines to create conditions that:

- Support the talents and agency of each young person

- Respect the culture and assets of the community

- Create personalized opportunities for growth

Building better conditions for learning and development will yield the robust equity we all seek in our learning and development ecosystems.8 Today, these ecosystems must be willing to embrace what we know about how young people learn and develop. The core message from diverse sciences is clear: The range of young people’s social, emotional, academic and cognitive skills and knowledge— and, ultimately, their potential as human beings—can be significantly influenced through exposure to highly favorable conditions. These conditions include learning environments and experiences that are intentionally designed to optimize whole child development.

The playbook, Design Principles for Community-Based Settings: Putting the Science of Learning and Development into Action, suggests how community-based practitioners can create these kinds of learning settings and points to engineering principles that build on the knowledge we have today to nurture innovations and systems change.

The field of youth work, or positive youth development, has embraced the five essentials of equitable whole child design for decades without using the term. Indeed, these essentials have flourished primarily in community-based civic, social justice, and youth programs and, in recent years, has been brought together into quasi-systems at the state and local level. The movement to take what was known about how children and youth learn and develop and use it as the starting point for programming and policy gained force in the early 1990s, with the seminal work of the Center for Youth Development and Policy Research.9 In 1992, the release of the Carnegie Council on Adolescent Development’s A Matter of Time report issued the seminal call to action for youth development. In that report, community programs to support youth development are described as: safe places that are relationship-rich, offering a sense of belonging, and help youth develop critical life skills such as decision-making and teamwork.10

Given the rich history of supporting positive youth development, many community-based settings do apply the principles to some degree but are challenged to do so fully for at least two reasons. First, the extent to which positive youth development is understood and practiced varies widely across the learning ecosystem. Second, many community-based settings lack the infrastructure support to implement practices consistently across the diversity of their sector. The playbook aims to address these challenges by setting forth common terms, definitions, and shared practices that can be used by community practitioners, technical assistance providers, and out-of-school time intermediaries in order to implement the science with quality and consistency, bringing intentionality to practice, and rigor to self-reflection so that all essential adults working in these settings are implementing science-informed practices aimed at transforming learning and development ecosystems.

1Vossoughi, S., Tintiangco-Cubales, A.G. (2021) (In Press) Radically transforming the world: repurposing education & designing for collective learning & well-being. Equitable Learning Development Project.

2The Readiness Projects (2021). Build Forward Together. https://forumfyi.org/the-readiness-projects/build-forward- together/

3Bruner, J. (1984). Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development: The hidden agenda. New Directions for Child Development , 23, 93–97.

4Stronge, J. H. (2018). Qualities of effective teachers. ASCD.

5Pledger, M. S. (2018). Cultivating culturally responsive reform: The intersectionality of backgrounds and beliefs on culturally responsive teaching behavior . UC San Diego. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4m44543x.

6Immordino-Yang, M. H., Darling-Hammond, L, & Krone, C. (2018). The brain basis for integrated social, emotional, and academic development . Aspen Institute.

7Stafford-Brizard, K. B. (2016). Building blocks for learning: A framework for comprehensive student development . Turnaround for Children.

8Osher, D., Pittman, K., Young, J., Smith, H., Moroney, D., & Irby, M. (2020). Thriving, robust equity, and transformative learning & development: A more powerful conceptualization of the contributors to youth success . American Institutes for Research and Forum for Youth Investment.

9Pittman, K. J., Center for Youth Development and Policy Research., & National Initiative Task Force on Youth at Risk (U.S.). (1991). Promoting youth development: Strengthening the role of youth serving and community organizations . Center for Youth Development and Policy Research, Academy for Educational Development.

10Carnegie Corporation New York. (1992). A matter of time: Risk and opportunity in the nonschool hours . Carnegie Corporation of New York.