DEVELOPING SKILLS, HABITS, AND MINDSETS AT THE CHESAPEAKE BAY OUTWARD BOUND SCHOOL

The Baltimore Chesapeake Bay Outward Bound School is a non-profit educational organization and expedition school that serves people of all ages and backgrounds through active learning expeditions and is located inside one of the country’s largest urban parks.

As part of their Character Curriculum, they have an activity called Alternate Ending: Historical Leaders which is focused on supporting young people to analyze a leader’s choice and response to a life challenge and identify how to utilize strengths to overcome challenges. In doing so, it helps young people reflect on their own leadership skills and attitudes and develop a growth mindset as they respond to challenging situations.

The activity starts with encouraging young people to think why some people are able to overcome a challenge while others give up. Young people are provided with short bios from different leaders. This is another space where adults can be more culturally responsive and provide bios of diverse leaders including those who belong to marginalized communities. This is also an excellent opportunity to challenge what is typically understood as leadership qualities and provide an opportunity for young people to expand the definition to be more inclusive of different styles of leaderships and leaders from diverse backgrounds.

Young people read the bios and are encouraged to respond to the following questions. The adult person first models these processes and then supports young people through the following steps.

- Identify the challenge and how the leader responded to the same. What did they do when faced with the challenge? What motivates them to persist?

- Reflect on three positive characteristics that the leaders used to respond to a challenge and contrast it with three negative characteristics that the leader could have used in an alternate reality.

- Create a hypothetical response that could have happened if the leaders were to use the negative characteristics to respond to the challenge. Write the fictional outcomes that the leader will face.

Young people can do this work in pairs or in small groups and share their reflections with their peers. The adult facilitates discussion around character traits, importance of persevering despite challenges, leadership, and responsibility that lead to specific outcomes and responses. This activity encourages critical thinking and problem- solving skills when faced with similar challenges.

Source: Adapted from Baltimore Chesapeake Bay Outward Bound School’s Character Curriculum titled, Alternate Ending: Historical Leaders. Available at https://www.outwardboundchesapeake.org/wp-content/uploads/Alternate-Ending-Historical-Leaders- Handouts.pdf

OVERVIEW OF DEVELOPING SKILLS, HABITS, AND MINDSETS

For young people to learn and thrive, they need ample opportunities to develop their whole selves. This, of course, includes expanding their knowledge and academic abilities, but also entails opportunities to develop the skills, mindsets, and habits that enhance their cognitive, emotional, and social growth.

Learning is tightly intertwined with one’s social, emotional, and mental state. For example, the emotions young people have while learning affects how deeply they engage with activities and content. Positive emotions, such as interest and excitement, open up the mind to learning. Negative emotions, such as fear of failure, anxiety, and self-doubt, reduce the capacity of the brain to process information and to learn. It is our emotions that engage us or shut us down, and it is the development of productive skills, habits, and mindsets that substantially drive our emotions.

Learner skills, mindsets, and habits also play a role in a young person’s academic development and well- being. For instance, when young people have developed skills for recognizing and managing their feelings and interactions and have developed productive dispositions and habits, including those related to a growth mindset, metacognition, and self-direction, they are better able to persist through challenges and to believe they can grow and succeed.

Developing these mindsets and habits also supports young people in developing positive and healthy identities that further enable them to grapple with the inevitable trials and tribulations that emerge in one’s daily life. Cultivating these strengths is accomplished by creating learning environments that welcome and value all young people and help them to develop positive integrated identities that affirm who they are, while they also learn skills that help them enact their purposes.

The Chicago Consortium on School Research’s Foundations for Young Adult Success Framework 1 offers a way to see how the development of skills, habits, and mindsets is related and develops over time. It illustrates what young people need to grow and learn, and how adults can foster their development in ways that lead to college and career success, healthy relationships, and engaged citizenship. It identifies three key factors to success:

- Agency, shaping the course of one’s life rather than simply reacting to external forces;

- Integrated identity, a strong sense of who one is, which provides an internal compass for actively making decisions consistent with one’s values, beliefs, and goals; and

- Competencies, the abilities to be productive, effective, and adaptable to the demands of different settings. These three factors rest on four “foundational components,” qualities that adults can directly influence:

- Self-regulation, the awareness of oneself and one’s surroundings, and management of one’s attention, emotions, and behaviors to achieve goals

- Knowledge and Skills, information or understanding about oneself, other people, and the world, and the ability to carry out tasks

- Mindsets, beliefs and attitudes about oneself and the world and the interaction between the two. They are the lenses individuals use to process everyday experiences

- Values, enduring, often culturally-defined, beliefs about what is good or bad and what one thinks is important in life. Importantly, to develop these foundational components, adults need to create opportunities for both active and reflective developmental experiences

The tumultuous times we face also underscore the importance of the intentional development of productive mindsets, skills, and habits. The COVID-19 crisis which began in the Spring of 2020 and ongoing instances of racial violence have stretched many to the breaking point, as they struggle with a precarious reality and the trauma that the events of the day have precipitated.

Enabling young people to develop the dispositions, habits, and skills to persist during trying times like these can mitigate the effects of the adversity that is felt by so many while enabling them to develop productive and civic-minded habits that can propel lifelong success and learning.

The Forum for Youth Investments’ David P. Weikart Center for Youth Program Quality (Weikart Center) provides a framework for how to develop critical skills, habits, and mindsets through its pyramid of program quality (see image below). The pyramid of program quality provides a simple framework for how adults can organize learning settings and build positive relationships to create opportunities for developmental experiences and skills development for all young people.

The pyramid of program quality is modeled after Maslow’s hierarchy of needs which suggests that individuals have different levels of needs that must be met before advancing to the next level. In particular, the notion that when physiological and safety needs are not met, people tend to have fewer resources to devote to other areas of life. It consists of four domains that define the quality of a learning setting beginning with safety, and building with supportiveness, interaction, and engagement, each representing sets of adult practices.

The practices highlighted under supportive and interactive environment in the pyramid of program quality are particularly important to develop critical skills, mindsets, and habits for social, emotional, and cognitive learning.

The practices highlighted under supportive environment includes practices such as explaining, supporting, and scaffolding activities, and helping young people to better understand their emotions. For example, helping them to recognize and be comfortable with their emotions and to process them in productive ways, or offering encouragement rather than praise in order to foster a growth mindset.

The practices related to creating an interactive environment focus on how adults can support learning experiences that occur through interactions with other people—both between adults and young people and between young people. Interactive learning environments often involve collaboration and small group discussion. This supports young people to build skills around empathy, such as how to work in teams and bridge differences.

WHY ARE CRITICAL SKILLS, HABITS, AND MINDSETS IMPORTANT?

WHAT THE SCIENCE SAYS

Learning is highly context sensitive. A young person’s skill and mindset development relies on an ongoing, dynamic interconnectedness between biology and environment, including relationships and cultural and contextual influences, resulting in significant variation within and across individuals over time. This contrast with the idea of universal, fixed steps or stages of development.

The norm is diverse developmental pathways—not missed opportunities but rather multiple opportunities to develop new skills and/or catch up. Because each learner’s development is nonlinear, with its own unique pathways and pacing that are highly responsive to positive contextual influences and support, the unique challenge for learning settings is to design personalized, supportive developmental learning experiences for all children and youth, no matter their starting point.

This extends to the development of social, emotional, and cognitive skills, which should be taught throughout childhood and adolescence and may need particular attention when young people face chronic, unbuffered stress due to adversity or oppression. In these cases, the development of foundational skills and mindsets, including self-regulation, stress management, and executive function, are at risk.

WHAT COMMUNITY-BASED SETTINGS CAN DO TO DEVELOP SKILLS, HABITS, AND MINDSETS

Supporting young people’s learning and development means supporting them in developing the capacities— skills, habits, and mindsets—to direct and engage in their own learning. These capacities include understanding of and growth in social and emotional learning skills, habits of mind for learning and persevering in learning, and sufficient health and wholeness to engage in the learning process. Simply put, these skills, habits, and mindsets contribute to readiness—”the dynamic combination of being prepared and willing to take advantage of life’s opportunities while managing life’s challenges.”2 A young person’s readiness is shaped by relationships, experiences, and environments—other essentials of equitable whole child design.

How to Develop Skills, Habits, and Mindsets

- Integrate social and emotional and cognitive skills into learning in culturally responsive ways

- Develop productive mindsets and habits

- Incorporate healing-centered practices

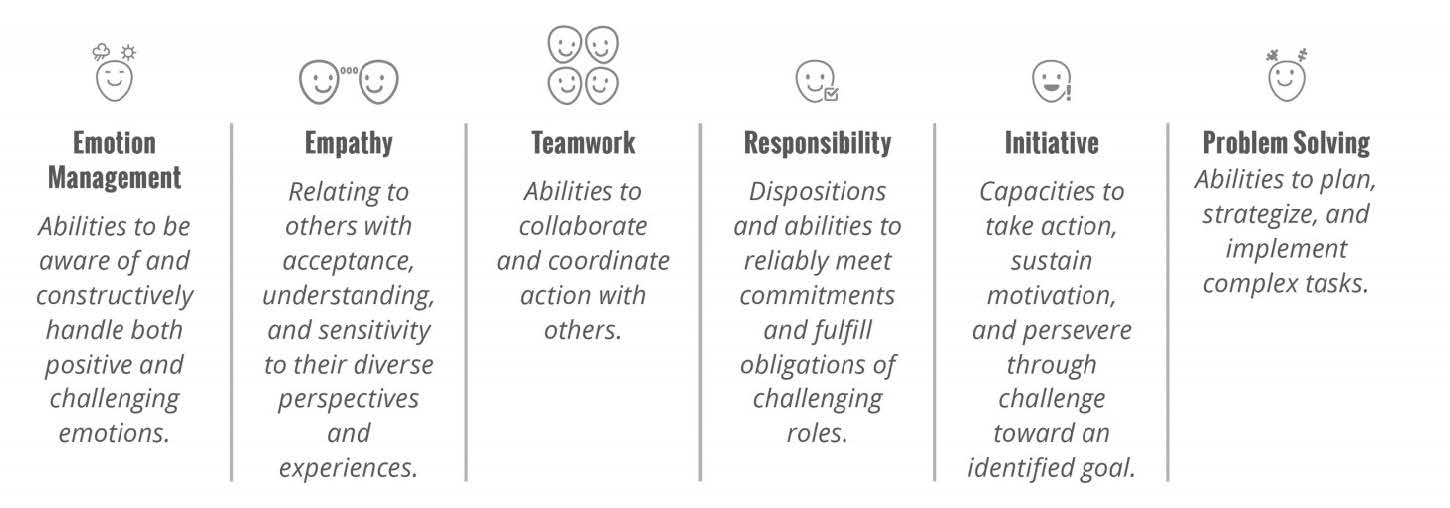

Weikart Center’s Preparing Youth to Thrive guidebook identifies promising practices for building social and emotional skills, habits, and mindsets and includes both specific youth experiences and staff behaviors that: appeared across eight out-of-school time (OST) programs; were described as important by expert practitioners; and were supported in the evidence base. Staff practices are defined broadly to include both staff behaviors that occur at crucial moments in response to situations that arise in the program, as well as behaviors that create norms and structures that staff build into their programs. These staff practices support the development of social, emotional, and cognitive skills, habits, and mindsets and are categorized under six domains: Emotion Management, Empathy, Teamwork, Initiative, Responsibility, and Problem Solving.

These six social emotional and cognitive competencies that young people develop cut across the two broad areas identified by brain research that are critical to children’s development: self-regulation skills (for example, self- awareness, emotion regulation, persisting through goals) and executive functions (for example, planning and organizing, revising and reflecting, staying focused despite distractions). Helping young people develop these capacities requires that social and emotional learning (SEL) is integrated into learning in culturally responsive ways that helps young people develop productive mindsets and habits in an environment that incorporates healing-centered practices.

Integrate Social, Emotional, and Cognitive Skills into Learning in Culturally Responsive Ways

Research shows that the best activities for social and emotional learning are sequenced, active, focused, and explicitly target certain skills.3 4 Afterschool programs that aim to intentionally promote social and emotional development have been shown to benefit young people in improving social and emotional skills and school performance. Using established evidence- based curriculum is one way to incorporate social, emotional, and cognitive skills into community-based programs. However, associated costs, strict program fidelity structures, and drop in based nature often make incorporating a curriculum incompatible with many community-based programs. Using small, easy to incorporate “kernels” as part of existing programming is another way.5 Positive youth development practices with an intentional SEL focus are described in the Social and Emotional Learning Program Quality Assessment, and can provide a framework for fostering young peoples’ awareness of their emotions and thinking processes as well as promoting self-regulation that helps them to manage emotions and not just suppress them.

Key Practices to Integrate Social, Emotional, and Cognitive Skills into Learning in Culturally Responsive Ways

Helping young people to identify and name their emotions is a basic social and emotional skill widely taught and practiced. This is a core part of emotional intelligence.6 Research has shown that when emotions are identified, especially when they are labeled with nuance and precision, they are easier to manage.

Managing emotions also helps with building empathy and inter-personal skills through developing perspective- taking and conflict resolution skills.7 In addition to helping young people become aware of their inner emotional world, the use of meta-cognitive thinking strategies like pausing, reflecting, and posing internal questions can help them to grow self-awareness and make the process of learning and skill development more visible to them. This metacognition, or thinking about thinking, and learning to learn, can be taught to young people by modeling and discussing these processes and providing young people with regular opportunities to reflect.

The Possibility Project (TPP) , is a creative-arts program based in New York that brings together diverse groups of teenagers to transform the negative forces in their lives and communities into positive action. It uses the performing arts and community action as way to build relationships across differences, resolve conflicts without violence, take on responsibility, and lead.

In the following example, a staff person from TPP illustrates how staff can provide a safe and supportive environment and support young people to be more self-aware of their emotions and understand causes and consequences. During this incident two young people got into a conflict about where they would stand on stage, and it escalated into a physical fight. One of the young people involved in this conflict had a history of several such incidents. She was devastated once she realized that she got into a physical fight once again and ran out of the room in tears. Afterwards, when the arts director invited a conversation to reflect, she was shaking and in tears. She reflected that she ran out of the room in tears because she suddenly felt terrible about attacking someone. She added that she had never felt this feeling before and had suddenly discovered the harm that she had done to many others and was unaware of what she had done. A production team member with whom she had grown close was intentionally with her throughout the day to ensure her safety, help her to describe her emotions and practice meta-cognitive skills, identify causes for why she felt anger and then remorse, provide her with agency to reflect on what she can do differently in the future, and to reassure her that she really did belong to the program and other peers have also made similar journeys like the way she was making on that day.

The development of self-regulation is a lifelong process and adults can support co-regulation by creating a safe and supportive environment. Adults can create and adapt structures to support young peoples’ processing of emotions and model healthy strategies that do not suppress expression but provides them with opportunities to discuss and learn from their ongoing emotional experiences. Better self-regulation ability supports young people in learning and maintaining social relationships. The need for practicing or learning self-regulation often occurs in-the-moment when strong emotions or distractions disrupt learning opportunities or pro-social participation. It is best when program staff can constructively intervene to support self-regulation and social-emotional growth when those teachable moments occur. Some moments of frustration and growth cannot be planned for. Adults can model healthy strategies such as active listening, channeling intense moments into action steps depending on the issue, and using problem-solving methods for conflict resolution.

Other practices that can be modelled by adults include communicating effectively about emotions, including their own and respectfully acknowledging and validating their emotions.8

An emphasis on emotional management and regulation can carry ideas that center the culture and behaviors of privileged groups and in turn, constrict the development and expression of young people’s full and authentic selves. Social interaction strategies like how we make eye contact or greet when we have different cultural norms around them that need to be included and discussed as adults support the development of young peoples’ social interaction skills. Integrating awareness and practices of social and emotional skills into community programs must be done in a context that is respectful to the culture and experiences of the young people participating.

It is important to be vigilant as to how social, emotional, and cognitive skills can be implemented in ways that uphold problematic norms that can enact or exacerbate psychological and emotional harm against historically marginalized groups, including black and brown youth and LGBTQ+ youth. What is understood as good behavior and ways to practice anger management needs to be questioned under the lens of racism, classism, sexism, ableism, etc. Supporting social, emotional, and cognitive skills is often used to equip young people to navigate unjust and oppressive structures. While these skills are important given the realities that young people face— the skill to question, challenge, and change oppressive systems (e.g., racism, sexism, ableism, etc.) needs to be as much or more of a focus as equipping young people to deal with them. Program staff need to recognize cultural differences in emotional expression and be aware of issues related to identity and structural oppressive systems that impact young people emotionally.

Developing Productive Mindsets and Habits

Young people’s beliefs and attitudes have a powerful effect on their learning and achievement. Holding negative perceptions of one’s ability to learn can quell motivation and create disengagement in learning settings. Conversely, productive dispositions can support youth in persevering through academic and personal challenges and put them on the road to academic success and holistic development. These key mindsets include:

- Belief that one belongs at school and/or learning setting

- Belief in the value of the work they are doing

- Belief that effort will lead to increased competence

- A sense of self-efficacy and the ability to succeed 9

Holding these beliefs about learning and one’s abilities is not innate. Rather, it is influenced and shaped by the interactions and environments in which young people learn and grow. Practitioners can help young people develop productive mindsets and habits by using growth- oriented language, providing opportunities for planning and goal settings, and supporting interpersonal skills.

Key Practices to Develop Productive Mindsets and Habits

Using growth-oriented language and practices includes adults encouraging young people to believe in themselves and framing challenge and failures as a typical part of the learning process10. Adults can use language that implies that hard work, persistence, and regrouping to try another strategy leads to greater learning and success. For instance, adults can say, the young person has not learned to do something “yet,” emphasizing the importance of continuing to try and persevering despite challenges. Adults can give specific feedback instead of general praise, or better yet, encourage young people to evaluate their own progress. Young people with confidence in their abilities to succeed on a task work harder, persist longer, and perform better than their less efficacious peers11.

A site coordinator at an afterschool program at Holmes Elementary School, Ypsilanti, Michigan through the Eastern Michigan University’s Bright Futures shared how she developed a “Makerspace” curriculum in partnership with the Hands On Museum at Ann Arbor, MI. The practices highlighted in the example below can easily be integrated into programming and other program models that community-based programs follow without necessarily following a specific curriculum.

Young people explore STEM concepts through hands-on building projects where they are expected to create to “the point of failure” in order to figure out for themselves what needs to change. During the “Make it Float” unit, young people were given certain materials and were explicitly told that all projects will fail, but it was their job to find the failure point and to then revise their structures.

Young people experienced many successes and many failures over the course of their projects, but the biggest change adults saw in them was a growth in their confidence, growth mindset, and creative problem solving. Young people went from saying “I can’t do it” or “This won’t work” to “I haven’t solved it yet” and “I haven’t figured out how to make it work yet.” The facilitators ensured that they were guiding young people with questions rather than with steps for completion. It took many repetitions for young people to get comfortable not having concrete steps and not having a “right” answer to work toward, but it led to more creative exploration and more of a willingness to try something new.

The development of interpersonal skills including social interaction skills, perspective taking, ability to work in teams, and resolve conflicts support young peoples’ ability to learn. Adults can support the development of empathy skills by providing structures where young people get to know each other, are able to relate to each other, listen and share personal stories, and become exposed to and experience diversity of identities, cultures, backgrounds, and experiences.

Adults can support young people to work together by co-developing norms and structure for collaborative learning, co-creating clearly defined and interdependent roles and responsibilities for young people to work together a shared goal. Adults can support young people by facilitating problem-solving strategies like backwards mapping, starting with a similar less complex problem, discussing through the steps to be taken, visualizing the problem by laying it out, and figuring out a plan for getting expertise and help from others.

Incorporate Healing-Centered Practices

A healing-centered approach focuses on creating a learning and developmental environment that prioritizes and fosters the well-being of young people, mitigating and helping to address negative emotions and behavior, stress, and creating an emotionally safe environment. The practitioner understands the nature of both environmental and individual causes of trauma and has working strategies to respond to the needs of a young person who has experienced either or both.

Adults understand that young people from marginalized communities often hold collective trauma because of economic, racial, and environmental injustice and harm. Adults support young people to understand the root causes of structural oppression and see young people beyond the trauma that engulfs them and supports them to heal.13

Key Ways to Incorporate Healing-Centered Practices

Strategies to promote physical and mental well-being are neither a quick fix nor about suppressing emotions or replacing negative emotions with positive ones. Physical and mental well-being is an act of self-compassion and self-respect to one’s whole being. It is about taking a pause, a breath, or a heartbeat to think, reflect, and discern the best course of action. Adults need to encourage young people to take that pause in a way that is respectful of the young person’s culture, background, and experiences. The idea is to not suppress anger, rage, etc. but to channel it to ask effective questions, understand root causes, and advocate for change.

A site coordinator from an afterschool program at the Perry Early Learning Center, Ypsilanti, Michigan, shared how their program incorporated Mindfulness Mondays into their schedule. This time consisted of games, activities, breathing exercises, five senses work, yoga, and meditation. They use resources and tools from the Sun Dance (kids’ version of the Sun Salutation), Go Noodle videos recommendations from Susan Kaiser Greenland’s The Mindful Child15 , and other meditation work such as body scans, mindful listening, mindful looking, mindful smelling, etc. These activities support young people to become more aware of the way they felt emotionally and physically in the present moment, which ultimately helps their emotion management and overall well-being.

SUMMARY

Learning is social and emotional. Young people need to be equipped with social, emotional, and cognitive skills to be able to learn and develop knowledge, skills, mindsets, and habits. Young people are not able to learn if they do not feel safe, are emotionally charged, or suppress their emotions in an unhealthy way. They need to learn to recognize all kinds of emotions, understand causes and consequences, and be provided with strategies to regulate and channel their emotions. It is essential that adults are inclusive and respect cultural differences as they help young people develop social, emotional, and cognitive skills. Using growth-minded language and practices helps young people to believe that they can overcome challenging tasks by trying, asking for help, planning, setting effective goals, and problem solving. They also need to experience working in teams and learn to build their interpersonal and social interaction skills. Adults can create structures that help young people to understand each other, listen attentively to the experiences and opinions of their peers, and build empathy. Young peoples’ physical and mental health are both important for their well-being. Far too many young people face one or the other individual, collective, or economic trauma or hardships. Adults need to be mindful of the collective trauma that young people from marginalized communities often hold. Young people need to be supported in way that respects them as people beyond their trauma.

WHERE TO GO FOR TOOLS AND RESOURCES

- The David P. Weikart Center for Youth Program Quality has developed various tools and resources to assess your SEL curriculum in terms of planning, designing and mapping your program’s content sequence and SEL sequence. These resources also include additional assessment tools to measure Youth SEL skills and staff SEL practices , and to measure program quality specific to SEL through the Social and Emotional Learning Program Quality Assessment. There are also specific guidebooks for supporting SEL skill development for both adolescents and children.

- The Collaborative for Social and Emotional Learning (CASEL) provides a suite on online tools, webinars, and resources to support implementation of high-quality evidence based SEL in programs.

- After School Matters provides community builders, energizers, and reflection activities for building social-awareness, problem solving, collaborations, personal mindset, and planning for success.

- Edutopia has curated resources including online kits, webinars, handouts, and articles that highlight strategies for addressing mindsets, persisting through challenges, understanding growth mindset, and how adults can give better feedback.

- Greater Good in Education provides strategies for both adult and young people’s well-being and how to create learning environments that are trauma-informed and healing centered.

- The National Center on Safe Supportive Learning Environments provides webinars and presentations for understanding trauma and its impact.

- The Education Trust offers recommendations for how to implement an equitable learning environment with an intentional focus on SEL and provides insights on how communities of color approach social, emotional, and academic development.

- Shawn A. Ginwright’s article on The Future of Healing: Shifting from Trauma Informed Care to Healing Centered Engagement describes the importance of shifting from trauma-informed care to healing centered engagement, which is strength-based, advances a collective view of healing, and re- centers culture as a key feature of well-being.

- America’s Promise Alliance’s brief on Creating Cultures of Care describes how trauma-informed practices support youth development and highlights how communities in Oregon and Missouri are engaging in this work.

FOUNDATIONAL SCIENCE OF LEARNING AND DEVELOPMENT RESEARCH

Developmental and learning science tell an optimistic story about what all young people are capable of. There is burgeoning scientific knowledge about the biologic systems that govern human life, including the systems of the human brain. Researchers who are studying the brain’s structure, wiring, and metabolism are documenting the deep extent to which brain growth and life experiences are interdependent and malleable.

Three papers synthesizing this knowledge base form the basis of the design principles for community-based settings presented here. For those seeking access to the research underlying this work, these papers are publicly available.

- Cantor, P., Osher, D., Berg, J., Steyer, L., & Rose, T. (2018). Malleability, plasticity, and individuality: How children learn and develop in context. Applied Developmental Science , 23(4), 307–337. https://doi.org /10.1080/10888691.2017.1398649.

- Darling-Hammond, L., Flook, L., Cook-Harvey, C., Barron, B. J., & Osher, D. (2019). Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development. Applied Developmental Science , 24(2), 97–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2018.1537791.

- Osher, D., Cantor, P., Berg, J., Steyer, L., & Rose, T. (2018). Drivers of human development: How relationships and context shape learning and development. Applied Developmental Science , 24(1), 6–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2017.1398650.

1Nagaoka, J., Farrington, C. A., Ehrlich, S. B., & Heath, R. D. (2015). Foundations for young adult success: A developmental framework . University of Chicago Consortium on Chicago School Research. https://consortium.uchicago.edu/publications/ foundations-young-adult-success-developmental-framework

2Krauss, S.M., Pittman, K.J., & Johnson, C. (2016). Ready by design: The science (and art) of youth readiness . Forum for Youth Investment. https://secureservercdn.net/50.62.195.83/0k2.28c.myftpupload.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/ readybydesign.pdf?time=1625313846

3Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., & Pachan, M. (2010). A meta-analysis of after-school programs that seek to promote personal and social skills in children and adolescents. American Journal of Psychology , 45, 294–309.

4Durlak, et.al, 2010; Smith, C., McGovern, G., Peck., S.C., Larson, R., Hillaker, B., Roy, L. (2016). Preparing youth to thrive: Methodology and findings from the social and emotional learning challenge . Forum for Youth Investment. https://www. selpractices.org/resource/preparing-youth-to-thrive-methodology-and-findings-from-the-sel-challenge

5Jones, S., Bailey, R., Brush, K., & Kahn, J. (2017). Kernels of practice for SEL: Low-cost, low-burden strategies . The Wallace Foundation.

6Goleman, D. (2005). Emotional Intelligence . Bantam.

7Stephan, W. G., & Finlay, K. (1999). The role of empathy in improving intergroup relations. Journal of Social Issues , 55(4), 729-743.

8Smith, McGovern, Larson, et al. (2016).

9Farrington, C. (2013). Academic mindsets as a critical component of deeper learning. University of Chicago Consortium on Chicago School Research.

10Dweck, C. S. (2008). Mindset: The new psychology of success . Random House Digital, Inc.

11Eccles J. S., & Roeser, R. W. (2009). Schools, academic motivation, and stage-environment fit. In Lerner, R. M., & Steinberg, L. (Eds.). Handbook of Adolescent Psychology (pp. 404-434). Wiley & Sons; Stipek, D. J. (1996). Motivation and instruction. In Berliner, D. C., & Calfee, R. C. (Eds.). Handbook of Educational Psychology (pp. 85–113). Macmillan.

12Smith, McGovern, Larson, et al. (2016).

13Ginwright, S. (2018). The future of healing: Shifting from trauma informed care to healing centered engagement. Occasional Paper , 25, 25-32.

14Center on the Developing Child. (2016). From best practices to breakthrough impacts: A science-based approach to building a more promising future for young children and families . Harvard University, Center on the Developing Child.

15Greenland, S. K. (2010). The mindful child: How to help your kid manage stress and become happier, kinder, and more compassionate . Simon and Schuster.