USER TIPS TO THE PLAYBOOK

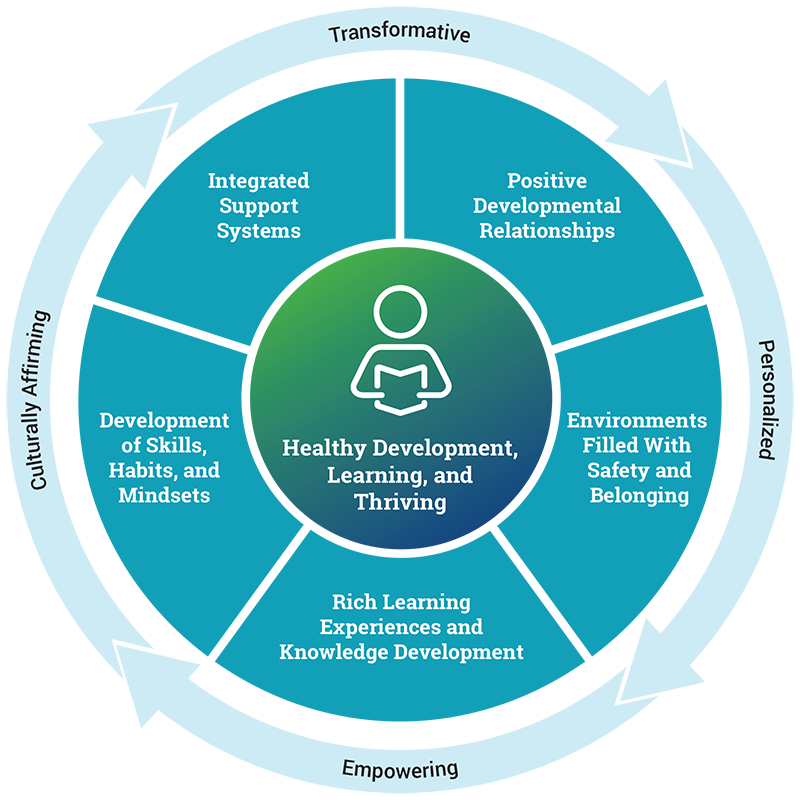

The Design Principles for Community-Based Settings: Putting the Science of Learning and Development into Action playbook provides the research-based rationale for why each of the five essential guiding principles for equitable whole child design matter for young people’s success and then describe a set of design principles and key practices that adults who work with young people in community-based programs settings could use to strengthen their practice. A curated list of resources where you can learn more about how to implement specific practices is included for each blue wheel component. This section of the Playbook provides guidance on where to start, given your community-based setting’s goals, priorities, and program structure.

INTENDED USERS

As described in A Typology of Community-Based Learning and Development Settings , the term community-based learning and development settings encompasses a wide range of community partners from national youth-serving organizations who are vast both in terms of reach and size to Jean’s Front Porch (literally a program on Jean’s front porch started to provide nutritious snacks, homework help, and supervised space for the kids on the block after school)—to everything in between including museums, libraries, workforce development programs, etc. As we widen our definition for community settings from traditional out-of-school time settings and consider the entire learning and development ecosystem, there are many settings (e.g., homes, classrooms, cafeterias, gyms, playgrounds, clubs, work places) with varying roles (e.g., librarians, docents, coaches and trainers, ministers and choir directors, theatre directors and music teachers, shift- supervisors at businesses that employ young people) who interact with young people.

APPLYING THE SCIENCE FINDINGS

Given the diversity of community settings and the roles, responsibilities, and experiences of the practitioners who work in them, means there is no one “right way” to apply science findings. This section of the Playbook provides tips on how to take some key steps in being able to put the science of learning and development into action in their community-based setting. Expand the tips below to learn more.

Quality implementation of the key practices highlighted in the playbook begins with establishing a shared vision for learning and development among the practitioners in your setting.

-

What are your goals for the young people who participate?

-

What are the potential barriers in being able to help them achieve those goals?

-

What are the core strengths of your setting?

-

How does the vision of high-quality learning settings that incorporate developmental practices highlighted in this playbook connect to your setting’s broader goals for the young people you serve?

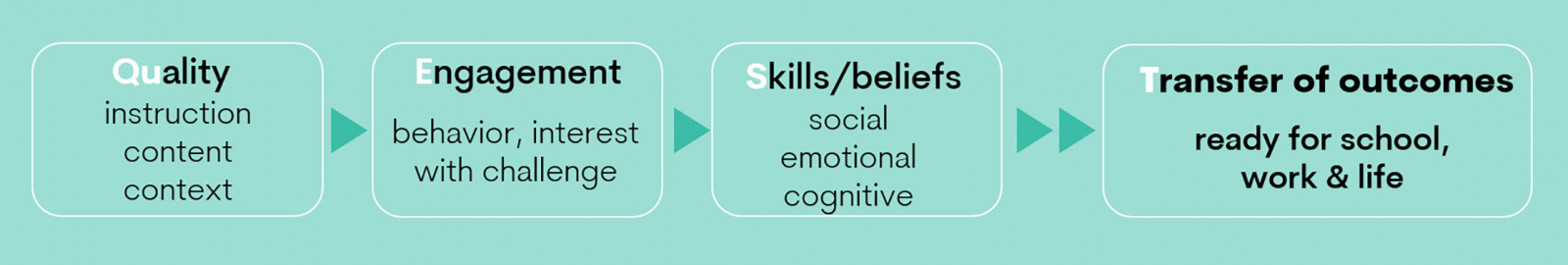

The QuEST model can be used to create a shared vision of quality for your program or setting by identifying key practices that adults will implement and the long term and short term skills, beliefs, and outcomes you want to develop for the young people you serve. The QuEST model articulates how time spent in settings rich with engaging content and high-quality staff practices increases youth engagement and contributes to positive short-term and long-term outcomes. It helps you to map your program strengths, identify gaps, align past efforts, and move towards identifying and setting shared goals.

As you dig identifying the quality of instruction, the content, or context of your setting, you may want to consider using the QuEST framework to think about what types of data, standards, and resources you use. How do you know that the young people you serve are engaged? What are the specific skills that you want young people to develop? What are the long-term outcomes that you want young people to have?

Depending on your role and how you identify your settings, there may be multiple levels of a system where you can influence practice, or none at all. Unlike K-12 systems that have training and accountability mechanisms in place for educators, the supports for community practitioners range from “none at all” to a robust quality improvement and credentialing system.

This means that your ability to influence how and how much you and others in your setting are able to apply the science of learning and development is shaped by factors that may be beyond your ability to control. Stand-alone programs like Jean’s Front Porch (described above) likely have limited capacity and resources to invest in training and support whereas if you are part of an out- of-school time system, or are part of a larger national youth-serving organization, you may have access to a quality improvement system that helps ensure that the adults working in your settings have the training and capacity to create quality learning and development settings that are putting the science into action.

What “essentials” are a priority in your setting?

One way to prioritize how to start digging into this work is to identify one or two specific essentials for equitable whole child design that your community-based setting leads with. For example:

-

You work or volunteer in a mentoring program that focuses on strong developmental relationships

-

You work of volunteer in a robotics program that helps youth learn critical skills

-

You work or volunteer in a public library running a reading club for middle school youth

-

You work or volunteer in a youth advocacy organization that focuses on youth voice and empowerment

What are the Dosage and Attendance Expectations and Patterns?

-

How frequently does a young person attend your program?

-

Given that frequency, what are the key practices you feel are the most important to implement?

-

What are potential barriers that you/your team would need to overcome for successful implementation?

What Mechanisms do you have in Place to Improve Access and Engagement?

-

How are you reducing barriers to participation so that all young people who want to participate are able to?

-

What are your outreach and recruitment strategies?

-

How are you helping family members understand the value of participating in community programs?

-

How would you engage families and caretakers as you consider an implementation plan for key practices?

The characteristics of the adults that interact with young people in a setting (e.g, credentials, demographics, experiences, interest, personal history, connections with the community) greatly affect whether and how they can implement science-informed practices. A common approach to ensuring that adults in a setting have the capacity to create optimal learning environments is to adopt a continuous program quality improvement process.

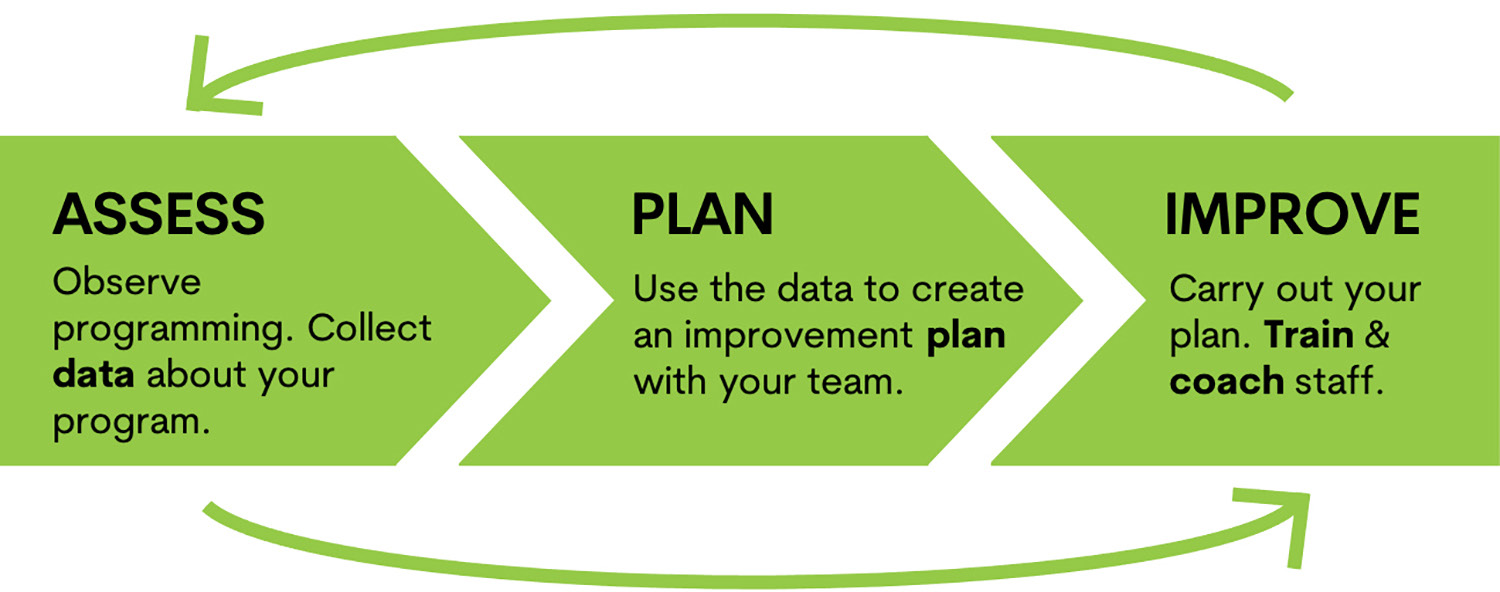

Focusing on building the quality of a learning setting can sometimes feel vague and intimidating. The Youth Program Quality Intervention (YPQI) represents years of research and field testing geared toward helping practitioners transfer engagement at the leadership level into concrete staff skills and tangible youth outcomes.

This approach helps programs continue to evolve, positioning improvement as an ongoing process rather than a one-time goal.

YPQI is an evidence-based continuous improvement process that uses an Assess-Plan-Improve cycle at the site level, as illustrated in Figure 5. A 2012 study of the YPQI demonstrated implementation of four practices— standardized assessment of instruction, planning for improvement, coaching from a site manager, and training for specific instructional methods—improves the quality of staff practices that children and youth experience.

The YPQI produces a cascade of positive effects beginning with provision of standards, training, and technical assistance, flowing through managers and staff implementation of continuous improvement practices, and resulting in effects on staff instructional practices.

If you want to intentionally implement the developmental practices highlighted in this playbook as an organization, then you may consider embedding a Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI) process like the YPQI approach described above, that provides supports in terms of training, technical assistance, and coaching to make the implementation process systematic and sustainable.

Building a CQI system includes developing a shared vision of high-quality implementation of practices and mapping how these practices lead to specific short-term and long-term outcomes for young people (e.g., using the QuEST model), assessing current implementation of these key adult practices, providing feedback, and accordingly providing targeted supports to adults to align their practices with the shared vision of high-quality. It is also important that participation in a CQI process is embedded and sustained in an organization.

Being more intentional about putting the science of learning and development into action is aided by considering your personal, organization, or system-level readiness to implement the design principles and related practices described in the playbook. Implementation readiness is a combination of:

- Your motivation to implement the principles and practices.

- The general capacities of your learning and development setting to implement the principles and practices. Capacity varies widely depending on whether you are a stand-alone program, part of a larger youth-serving organization, or have an out-of-school time system already established to support your adult capacity-building efforts.

- The specific capacities that you will need to implement the principles and practices.

This simple R=MC2 approach1 to thinking about readiness, where R refers to readiness, M refers to motivation, and C refers to the two kinds of capacity— general and specific, can help you “right size” your approach to improving practice so you don’t take on too much and risk not implementing what you have the capacity to do well.

Readiness considerations are useful prior to implementation; however, the road to readiness is cyclical, not linear. Readiness-focused thinking is intended to inform continuous improvement. You may move back and forth in your readiness to implement the five essential guiding principles as you recalibrate and improve the quality of their implementation. As such, even if you already do implement aspects of whole child design in your learning and development setting it may be useful to consider the current state of readiness (i.e., motivation and capacity) to see if there are opportunities for improvements that will ultimately ensure successful implementation.

GETTING STARTED WITH A REFLECTION TOOL

The five tips offered above will take some time for you, your organization, and/or your larger network of community-based settings to consider. But if you are looking for a place to just get started and see where your community-based setting is in terms of putting the science of learning and development into action, the simple self-reflection tool helps you think about how important the practices are to your setting and how well you think your setting is implementing them. Addressing the questions below may help you identify a few practices based on what you want to strengthen and/or improve. You can then find information, example, and resources related to those practices in the Playbook chapters.

- What practices related to the five essential guiding principles of the blue wheel do you think your program does well?

- How do you know how well you are doing them? What qualitative or quantitative evidence do you have?

- What practices would you like to improve and why? What is the problem that you are trying to solve?

- What other conditions for learning do you/your team consider critical to for your work with young people How would you integrate those practices?

- How do these key practices align with standards already established in the program?

- What resources would you/your team need to implement key practices?

Figure 6: Design Principles for Community-Based Settings - Reflection Tool Download as PDF

|

Instructions: Using the columns on the right, rate each of the below categories from 1 (low) to 5 (high) on how important you feel it is and how well it is currently being practiced in your community-based learning and development setting. |

How Important?

1 (low) – 5 (high)

|

How well is it practiced?

1 (low) – 5 (high)

|

|

|

POSITIVE |

Form developmental relationships between adults and young people that promote leadership and help young people discover their strengths, expand their possibilities, and challenge growth |

|

|

|

Foster relationships among young people by providing opportunities to lead and mentor. |

|

|

|

|

Cultivate relationships with family members using a strengths-based lens that provides opportunities for engagement and collaborative decision-making |

|

|

|

|

ENVIRONMENTS |

Cultivate safety and consistency , implementing routines that support risk- taking, helping young people build personal connections and a sense of purpose for themselves, Use restorative practices to help young people to reflect on any mistake, solve conflicts, and get counseling when needed |

|

|

|

Build community using positive behavior management practices, fostering positive peer to peer relationships, and co-developing program expectations with young people. |

|

|

|

|

Be culturally responsive and inclusive , using affirmations that establish the value of every young persons’ many identities and abilities, building on the diversity and cultural knowledge of young people and their families, and developing young people’s knowledge, skills, and agency to critically engage in civic affairs. |

|

|

|

|

RICH |

Use scaffolding and differentiation techniques to support individual learning styles, assessing and adjusting programming to fit the interests, strengths, and needs of young people while providing asset based personalized supports as well as fostering co-operative learning. |

|

|

|

Facilitate inquiry-based approaches to learning to help youth be active learners, providing regular and thoughtful feedback and creating opportunities for young people to reflect and revise. |

|

|

|

|

Adopt a culturally responsive approach to learning by explicitly connect students’ diverse experiences and cultural assets with program content, promote racial-ethnic identity development, voice, and agency, and facilitating conversations around equity and social justice. |

|

|

|

|

DEVELOPMENT OF |

Integrate social and emotional learning in a culturally responsive context, fostering awareness and understanding of young peoples’ emotions, providing them with strategies that supports them to both express and manage emotions, and doing so in a way that ensures cultural sensitivity and responsiveness. |

|

|

|

Develop productive mindsets and habits by nurturing growth mindset, providing opportunities for planning and goal setting, and supporting interpersonal skills like empathy, collaboration and problem solving. |

|

|

|

|

Incorporate healing-centered practices , employing responsive strategies based on the principles of safety, trust, collaboration, choice, and empowerment and promoting physical and mental well-being through mindfulness strategies, breathing exercises, and other stress. |

|

|

|

|

INTEGRATED |

Connect youth to supplemental learning opportunities by partnering with schools to provide seamless and aligned supports, monitoring young people’s academic growth, and adding adult capacity to the school day. |

|

|

|

Promote access to other supports and opportunities that foster health and well-being by ensuring mechanisms and partnerships are in place to connect families and youth to basic needs such as food, health, and mental health in addition to academic supports and participating in whole-school comprehensive community partnership models. |

|

|

|

1Scaccia, J. P., Cook, B. S., Lamont, A., Wandersman, A., Castellow, J., Katz, J., & Beidas, R. S. (2015). A practical implementation science heuristic for organizational readiness: R=MC2. Journal of Community Psychology , 43(4), 484-501.