CREATING RICH LEARNING EXPERIENCES AND KNOWLEDGE DEVELOPMENT THROUGH AN EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING MODEL AT 4-H.

4-H is a national youth development organization whose mission is to give all youth equal access to opportunity.

4-H is a national youth development organization whose mission is to give all youth equal access to opportunity.

4-H provides kids with community, mentors, and learning opportunities to develop the skills they need to create positive change in their lives and communities. It focuses on hands-on projects in health, science, agriculture,

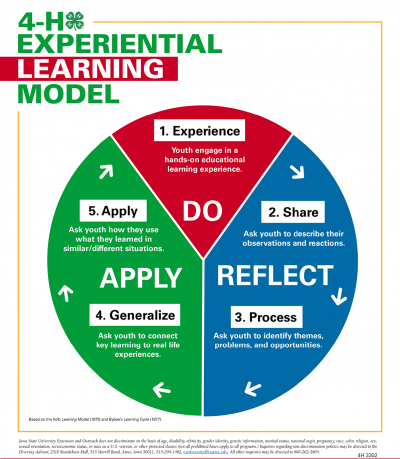

and civic engagement. It relies heavily on a five-step experiential learning model that volunteers can use to facilitate educational 4-H activities. “Learning by doing” is a commonly used expression in 4-H. It focuses on using inquiry-based strategies to support active learning. The five steps of their experiential learning model are:

Step 1: Experience. Youth engage in a hands-on educational learning experience. This step focuses on the importance of young people being actively involved and at the center of the learning experience. The young person is encouraged to learn by doing and provided with guidance and feedback by the adults. Adults encourage young people to problem solve by asking if-then and open-ended questions.

Step 2: Share. Youth are asked to describe their observations and reactions based on what they did/experienced during Step 1. Adults ask them questions on what they did, saw, felt, heard, etc.

Step 3: Process. Youth are asked to identify themes, problems, and opportunities. This is also an opportunity for the adults to help facilitate a debriefing of the experience. Adults ask open-ended questions to help them reflect on their experience, discussing what went well, what were the problems they faced, and what could be done differently next time. This is also an opportunity for adults to listen effectively to understand the young person’s thought process and provide feedback to support the young person’s unique style of learning.

Step 4: Generalize. Youth are asked to connect key learning to real life experiences. In this step, 4-H emphasizes the need for young people to be able to make a personal connection to the learning experience. The adults ask questions focused on what they learned, how it relates to other topics they learned in the past, or are learning at present.

Step 5: Apply. In the final step of this process, youth are asked how they may use what they learned in a similar or different situation. They are then asked how their learning relates to other settings in their lives and are encouraged to think how they can use what they have learned in other situations in the future.

Source: Adapted from Norman, M. M., & Jordan, J. C. (2006). Using an experiential model in 4-H . EDIS, 2006(9).

OVERVIEW OF RICH LEARNING EXPERIENCES AND KNOWLEDGE DEVELOPMENT

Learning is a function both of teaching—what is taught and how it is taught—and youth perceptions about the material being taught and about themselves as learners. Young peoples’ beliefs, emotions, and attitudes have a powerful effect on their learning and achievement. Motivation is also critical to learning. Young people will work harder to achieve understanding and will make greater progress when they are motivated to learn something. However, motivation is not just inherent; rather, it can be nurtured by skillful teaching and coaching.

Practitioners that successfully motivate young people to engage in learning provide both meaningful and challenging work, within and across disciplines that build on young peoples’ culture, and prior knowledge and experience. Young people learn best when they are engaged in authentic activities and collaborate with peers to deepen their understanding and transfer of skills to different contexts and new problems.

With these goals in mind, rich learning experiences and knowledge development can be supported by inquiry-based learning structures with thoughtfully interwoven instruction and opportunities to practice and apply learning, meaningful work that builds on youth’s prior knowledge; experiences that are individually and culturally responsive, and well-scaffolded opportunities to receive timely and helpful feedback.

WHY ARE RICH LEARNING EXPERIENCES AND KNOWLEDGE DEVELOPMENT IMPORTANT? WHAT THE SCIENCE SAYS

Research from the science of learning and development shows that people learn by building on their prior knowledge and experiences, drawing on their individual, cultural, and community contexts, and connecting what they are learning to what they already understand. In order to make meaning of new ideas, individuals need to apply them to new contexts. People are also motivated to learn by questions and curiosities they hold—and by the opportunity to investigate what things mean, and why things happen. Below are the key findings from science that can inform practice.

WHAT COMMUNITY-BASED LEARNING AND DEVELOPMENT SETTINGS CAN DO TO CREATE RICH LEARNING EXPERIENCES AND KNOWLEDGE DEVELOPMENT

There are three primary ways that community-based learning and development opportunities can co-create rich learning experiences and knowledge development. First, they can use scaffolding and differentiation techniques to support each young person’s individual learning style. Doing so also means that practitioners use inquiry-based approaches to learning that help young people be active and engaged learners. Adults also can adopt a culturally responsive approach to learning

How to Support Rich Learning Experiences and Knowledge Development

- Use scaffolding and differentiation techniques to support individual learning styles

- Use inquiry-based approaches to learning to help youth be active learners

- Use culturally responsive approaches to learning.

Use Scaffolding and Differentiation Techniques

The key to helping youth be successful learners is to keep challenge and frustration at levels that support growth and perseverance and to relate to youth in a way that empowers them. Adults can support learning by scaffolding, breaking down tasks, providing choice, and adjusting the program and activities to fit the interest, strengths, and needs of the young people. Secondly, practitioners can differentiate supports so that they are personalized to every youth. For community-based learning and development settings that engage groups of youth (afterschool programs, sports clubs, museum programming) practitioners need to consider group management and dynamics in order to foster cooperative learning.

Key Practices to Support Scaffolding and Differentiation

Adults should work together with young people to ensure that the learning experience fits their interests and needs. Adults may need to monitor the level of challenge, tailor supports accordingly, and encourage leaner agency. It may involve breaking down tasks into smaller steps, asking effective questions, ensuring young people connect with prior learning, modelling problem solving skills, and providing choice and voice to pursue tasks according to their interests, among others.

AHA! (Attitude, Harmony, Achievement), Girl’s Relationship Wisdom Group guides teens to set goals and stop bullying and hatred and is delivered in a group mentorship setting. Adults work with young people to identify personal goals that fits their interests and strengths. Some of the questions that they ask throughout the semester include:

- What do you need help with?

- What are the biggest things you are having to overcome from your past?

- Where in your life right now do you feel like you are off course and need support to get back on track?

- If there was one thing in your life you could really transform, what would it be—a habit, something you’re doing that you’re not proud of?

- What’s the thing you have the hardest time talking about?

An asset or strengths-based approach is rooted in the principle that all young people have great potential, every young person learns and develops differently, and development is progressive and continuous. All adults should hold high expectations of all young people to attempt higher levels of performance through perseverance. Practitioners that empower young people to identify their strengths and needs can motivate and support them to constantly improve their skills and abilities. This approach to supporting young people recognizes that every young person learns and responds differently and has different strengths, and that systematic oppression may inhibit equitable outcomes for all.

The Philadelphia Wooden Boat Factory is an apprenticeship based maritime educational program. It uses a strength-based process to effectively scaffold young people and support them to stay motivated and persevere through challenging tasks. Program staff often hear youth saying they are not good at math when they need to use math skills to build or sail the boat. The adults adopt a strength-based approach that focuses on subtle but important changes when they interact with young people. They use both formal and informal opportunities to explicitly provide examples of their strengths and hold them to high expectations. This helps young people to know that they have a champion who believes that they can overcome the challenge and it motivates them to improve. The actual gains may sometimes be modest, but they have seen young people’s pride soar when they are acknowledged for the work they have accomplished. Young people feel motivated to push even further. The adults in the program know that motivation cannot be provided through a fancy speech nor just good advice. Young people need to feel empowered and if their autonomy is negated, it may undermine how they value their own competence. (Note: as the time of the Playbook’s publication, the Philadelphia Wooden Board Factory was no longer operating.)

Adults can structure groups in a way where young people are both having fun and are motivated to learn together and from each other in an emotionally and physically safe learning environment. Well managed group work has co-developed expectations and provides multiple opportunities for young people to work together in different group sizes and group formations according to their interests, strengths, and needs. Well managed group work also provides clear roles (e.g., facilitator, record-keeper, timer, spokesperson) and responsibilities that requires interdependence for the group members to be successful in completing the task. These group structures also help in learning as the content is more scaffolded, young people have opportunities to talk to each other and think together regarding the real-world problem they are solving together. These meta-cognitive and meta-strategic skills also help in better retention of knowledge that helps in learning more effectively.

For cooperative learning to be successful, adults also need to model these skills and facilitate a shared understanding of the purpose and goals of the group. These collaborative group structures also help in building empathy, problem-solving, etc., which are highlighted in the chapter on skills, habits, and mindsets.

Wyman's Teen Outreach Program (TOP), based in St. Louis, Missouri, emphasizes the importance of rituals and practices to promote a sense of group identity and cohesion. They emphasize the need to include getting-to know-you icebreakers and games to help all young people feel welcome and begin to form a group. Adults use name games, team-building activities, and other challenges that let young people get acquainted with each other, with the organization, and with all facilitators. These structures facilitate the development of positive relationships among young people and help them to learn from one another as they work as groups and solve real-world problems. This also helps in improving young peoples’ intrinsic motivation and attendance, and they ultimately learn better. For example, youth at Wyman cook monthly meals for family members of cancer patients who are undergoing treatment at a local facility. This project involves planning, preparing, serving, and storing food for large groups as well as considering the unique needs of participating families. It provides opportunities to solve real-world problems by talking through problems supporting metacognitive and meta-strategic skills that is known to improve learning and academic outcomes.

Use Inquiry-based Approaches to Learning

Inquiry-based learning requires young people to take an active role instead of a passive role. This means going beyond receiving and memorizing information provided to them. Community-based programs, because of their voluntary nature, provide young people with a wide range of choices and thereby are well-poised to let young people take charge of what questions or problems they are curious about and want to investigate and analyze. Practitioners can support them by asking effective questions that enable them to problem solve, think through various considerations of possibilities and alternatives, and apply that knowledge in various settings.

Key Practices to Support an Inquiry-Based Learning Approach

Active learning involves young people exploring problems and projects that they are interested in and reaching solutions by experimenting with multiple methods of inquiry and problem-solving across various types of community learning and development opportunities. These problems and projects benefit from being about real-world issues where young people are working collaboratively to solve complex problems. It requires them to take a more interdisciplinary approach and think holistically about the problem they are solving. An effective way to guide young people is to ask open-ended and if-then questions to define the problem, analyze, make connections with their previous experiences, make comparisons and inferences, generate solutions, and apply knowledge to solve problems. Asking questions to young people also enables practitioners to understand gaps in knowledge and accordingly adjust supports.

YW Boston Youth Leadership Initiative , a project of YWCA Boston, Massachusetts, engages young people from high schools across the Boston area in the development of community action projects that address inequity in their communities, schools, and neighborhood. For example, a delegation at one school wanted to create social justice workshops for their classmates but were unable to gain support from the school administration. They were concerned they would not be able to build enough youth participation in the workshops. At a biweekly meeting, the adults helped the delegation walk through an inquiry based critical thinking process in which they matched the resources available to them to the needs of their project. Through this process they identified a teacher who they could use as a faculty liaison. They also created a plan for building youth participation (reaching out to affinity youth groups, e.g., Gay/Straight Alliance), using their personal networks, and a social media campaign.

Regular, well-designed feedback on young people’s work is a critical support for learning and development.2 Without feedback about conceptual errors, the learner is likely to persist in making the same mistakes. In addition, the quality of the feedback is key. Studies find that gains are most likely to occur when feedback focuses on features of the task and emphasizes learning goals whereas neither nonspecific praise nor negative comments supported learning.3

Giving specific and descriptive feedback lets young people know exactly what they did well so they can repeat or build on it. It also recognizes their effort and improvement. Simply asking a young person to describe or explain what they have done, suggesting options, and asking questions that make them consider other alternate solution are all forms of giving thoughtful feedback. However, practitioners should also support young people in receiving the feedback provided to them and ask if there are any barriers that restrict them from applying the feedback.

Having opportunities to revise one’s work in light of the feedback they receive is another important support for the learning experience. Revision of work is a critical aspect of the learning process, supporting reflection and metacognition about how to approach a particular kind of content or genre of tasks in future learning.

Unless young people have opportunities to incorporate the feedback as they revise their work or performance, they cannot benefit optimally from the feedback that practitioners or their peers often take considerable time and effort to produce.

Use Culturally Responsive Approaches to Learning

Culturally responsive learning environments celebrate the unique identities and backgrounds of all learners, while building on their diverse experiences to support rich and inclusive learning.4 This asset-based orientation rejects the idea that practitioners should be colorblind or ignore cultural differences, as these orientations can have harmful effects on learning and development. Instead, culturally responsive practitioners place young people at the center by inviting their multifaceted identities and backgrounds into the learning setting to inform content, instruction, and learning structures.5 Culturally responsive practitioners recognize the importance of infusing young people’s cultural references in all aspects of learning.6 Doing so enables practitioners to be responsive to learners—by validating and reflecting the diverse backgrounds and experiences young people bring and also by building upon their unique knowledge and schema to propel learning and critical thinking. As practitioners implement culturally responsive approaches to teaching and learning, they have to be learners themselves of new cultures, new languages, and new traditions to foster and nurture linguistic, literate, and cultural pluralism and equality.7 Responding to and sustaining young people’s cultures and backgrounds is necessary given the harsh fact that many marginalized young people in the U.S. have been subject to deficit approaches to teaching and learning, which have often sought to minimize, penalize, or eradicate the languages, literacies, and cultural ways of being that do not adhere to white, middle-class norms. Given this history and reality, culturally responsive approaches that center and celebrate diversity can disrupt these problematic tendencies while furthering belonging and inclusion.8

What is understood as normative in terms of knowledge, beliefs, or culture has been created by those in positions of power and continues to perpetuate if unchallenged. When adults create spaces for young people from marginalized communities to become active participants in the process of creating knowledge, it helps in dismantling this knowledge-power nexus. It is also not just about creating awareness among young people of injustices but a critical examination of the structural oppressive forces and the knowledge-power-privilege nexus that systematically works against marginalized communities, especially for our brown, black, and indigenous young people. It is about empowering them with critical cognitive skills to decolonize their minds, challenge existing socio-political and historical structures that control them, recognize that nothing is inherently wrong with them, and gearing them towards action.

This means recognizing and broadening the definition of learning and skill development to incorporate the skills that young people from marginalized communities develop as they constantly negotiate and problem solve.

Culturally responsive approaches also support young people’s development and learning. In its attention to developing a young person’s sense of belonging, agency, and purpose, there is evidence that these approaches positively affect educational outcomes, including academic achievement, engagement in learning, and racial identity development. 9 Furthermore, learners from all backgrounds benefit from inclusive learning environments that honor and celebrate diversity and inclusion.

These settings can not only help all young people learn and embrace the diverse backgrounds and cultures that make up the fabric of U.S. democracy, but also cultivate their awareness and orientations toward issues of injustice.

Cultural responsiveness in learning settings can be cultivated through rich learning experiences that build bridges between young people’s experiences and program content; promote racial-ethnic identity development, voice, and agency; and facilitate critical conversations around equity and social justice.

Key Practices to Support Using a Culturally Responsive Approach to Learning

Positive development is about supporting young people to be agents of their own development, with support from adults. When young people who belong to historically marginalized communities are provided with opportunities to develop their racial-ethnic identity, it helps them to gain a sense of self and agency to questions negative biases and stereotypes about them. Fostering youth voice involves findings ways for young people to actively participate in shaping the decisions that affect their

Neutral Zone in Ann Arbor, Michigan is a youth- driven center founded by a diverse group of teens to provide a space for social, cultural, educational, and creative opportunities to high-school teens. They established a Teen Advisory Council (TAC) to create an ongoing structure that advocates for meaningful youth voice across all the programs that Neutral Zone offers. In 2003, the TAC recognized that Neutral Zone programs consistently needed money to help achieve their goals and so added fundraising to its focus. In 2004, the TAC hosted a Gala event generating approximately $3,000. They then created a system for distributing funds to support other programs at the Neutral Zone. Since that time, the TAC continues to raise and grant funds on an annual basis. In 2007, TAC members participated in the annual Neutral Zone program evaluation. Following a successful program evaluation in 2008, TAC became a standing committee of the Board of Directors, replacing the Program Committee, which was mostly comprised of adults. The TAC defines its purpose as: to drive Neutral Zone’s program success through program approval, fundraising, grant-making, and evaluation. As part of the Council, young people build community, plan for the year, host meetings and activities that are meaningful to them, reflect on activities through the year, and recruit participants for the following year.

Culturally responsive environments engage learners in project-based learning that asks them to critically analyze issues of injustice and take action to impact change.12 These projects, which are grounded in the pursuit of social justice and explore the depths of systemic power and oppression, often launch by posing an essential question or equity-focused problem to young people or by asking them to identify equity issues impacting them and their communities. Young people have an authentic audience and purpose for their work and use their learning to impact change.

Community-based learning projects are one way practitioners can immerse young people in this form of rich and culturally responsive learning. As the term suggests, community-based learning allows young people to learn in and from their own communities by providing them opportunities to acquire, practice, and apply subject knowledge and skills in their neighborhoods and local surroundings. These projects often include problem- solving around a local issue or concern and give young people opportunities to develop productive mindsets wherein they see themselves as agents of change while deepening their knowledge and skills.13

Assata’s Daughters is a black, women-led, young people directed organization that organizes Black young people in Chicago by providing them with political education, leadership, mentorship, and revolutionary services. They organize training opportunities for young black people to use their practical experience, build and or to work with coalitions throughout the city to tackle city-wide issues. They work with and for neighborhood which is where they locate as the real agents of power and change. The have several programs. For example, responsive organizing, environmental justice, training programs, and youth organizers through which they receive lessons on the tactics and strategies that can be used to address specific social issues like gentrification, police in schools, and capitalism. The young people who participate in these programs also receive training in urban farming and food justice and also learn basics of gardening, land conservation, food justice, and the importance of self-sustainment as a tool of resistance.

SUMMARY

The science is clear that learning and development is not linear. It is a progressive and continuous and it is crucial now more than ever before that all young people have access to rich learning experiences and knowledge development. Young people need to be in learning settings where every adult believes that every young person has great potential and the learning environment needs to be aligned to their strengths, interest, and needs. Young people can attain mastery of complex knowledge and skills when they are provided with opportunities to learn by experiencing, sharing, reflecting, and revising; solving real-world problems; and they take an active role in constructing knowledge and build on their prior experience and knowledge.

It is also crucial to adopt a culturally responsive approach to learning so that the diverse experiences and cultural norms of young people from historically marginalized communities are brought to the center to help them connect previous and new knowledge and to learn more efficiently. Young people also need opportunities to be active learners where instead of just receiving or memorizing information they are questioning, investigating, and analyzing to solve real problems and advocate for social justice and equity.

They are working on project that are of interest to them and are personally meaningful to their sense of self and identity. In a rich learning experience, every young person feels motivated to problem solve and persevere despite challenges. They are provided with guidance and feedback that is supportive and strengths based. Young people are supported as they are challenged to try new skills and understand that mistakes are part of the learning process. Adults assess and adjust programming to fit the needs of young people and provided with structures for effective group work and collaborative learning.

TOOLS AND RESOURCES TO CREATE RICH LEARNING ENVIRONMENTS

- Students at the Center Learning Hub provides a framework and resources for personalized learning, developing student agency and voice, competency-based education, and learning that supports the real-world experiences of young people and enables them to see connections.

- The Weikart Center's guidebook for Cooperative Learning and Active Learning lists several activities along with additional resources to support and inquiry based approach to learning as well as scaffolding and differentiation strategies. The Weikart Center also provides assessment tools to assess quality of learning environments and identify training needs.

- The National Center for Quality Afterschool has resources and tools for creating rich learning experiences around literacy, math, science, homework help, technology, and the arts.

- Sanford Education Programs at National University provides lesson plans and activities for pre-K- grade through grade 6 to create connected and inclusive learning settings.

- Education Reimagined provides resources for creating a learner-centered environment.

- Abolitionist Teaching Network provides various anti-racist teaching tools including podcast, ted talks, and tools to support creation of an anti-racist learning experience and knowledge development.

- Culturally Responsive Education Hub provides resources and videos on practicing culturally responsive educations.

- AfterSchool KidzLit resources provides for how to use literature and activities to build reading skills, deepen thinking, and abilities to work in teams by honoring diversity and viewpoints of others. It also provides video tutorials on practices related to engaging youth voice, engagement, and learning.

FOUNDATIONAL SCIENCE OF LEARNING AND DEVELOPMENT RESEARCH

Developmental and learning science tell an optimistic story about what all young people are capable of. There is burgeoning scientific knowledge about the biologic systems that govern human life, including the systems of the human brain. Researchers who are studying the brain’s structure, wiring, and metabolism are documenting the deep extent to which brain growth and life experiences are interdependent and malleable.

Three papers synthesizing this knowledge base form the basis of the design principles for community-based settings presented here. For those seeking access to the research underlying this work, these papers are publicly available.

- Cantor, P., Osher, D., Berg, J., Steyer, L., & Rose, T. (2018). Malleability, plasticity, and individuality: How children learn and develop in context. Applied Developmental Science , 23(4), 307–337. https://doi.org /10.1080/10888691.2017.1398649.

- Darling-Hammond, L., Flook, L., Cook-Harvey, C., Barron, B. J., & Osher, D. (2019). Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development. Applied Developmental Science , 24(2), 97–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2018.1537791.

- Osher, D., Cantor, P., Berg, J., Steyer, L., & Rose, T. (2018). Drivers of human development: How relationships and context shape learning and development. Applied Developmental Science , 24(1), 6–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2017.1398650.

1Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., Cocking, R. R., Donovan, M. S., & Pellegrino, J. W. (2004). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school . National Academies Press.

2Thorndike, E. L. (1931/1968). Human learning . The Century Co.

3Kluger, A. N., & DeNisi, A. (1996). Effects of feedback intervention on performance: A historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychological Bulletin , 119(2), 254–284.

4Stronge, J. H. (2018). Qualities of Effective Teachers . ASCD.

5Pledger, M. S. (2018). Cultivating culturally responsive reform: The intersectionality of backgrounds and beliefs on culturally responsive teaching behavior . UC San Diego.

6Ladson-Billings, G. (2009). The Dreamkeepers: Successful teachers of African American children . John Wiley & Sons.

7Paris, D. (2012). Culturally sustaining pedagogy: A needed change in stance, terminology, and practice. Educational Researcher, 41 (3), 93-97.

8Powell, J. A., & Menendian, S. (2016). The problem of othering: Towards inclusiveness and belonging. Othering & Belonging, 1 , 14-39.

9Brown, M. R. (2007). Educating all students: Creating culturally responsive teachers, classrooms, and schools. Intervention in School and Clinic, 43 (1), 57-62.

10Roeser, R. W., Eccles, J. S., & Sameroff, A. J. (1998). Academic and emotional functioning in early adolescence: Longitudinal relations, patterns, and prediction by experience in middle school. Development and Psychopathology , 10, 321–352. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0954579498001631.

11Reeve, J., & Jang, H. (2006). What teachers say and do to support students’ autonomy during a learning activity. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98 (1), 209–218. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.98.1.209

12Duncan-Andrade, J. M. R., & Morrell, E. (2008). The art of critical pedagogy: Possibilities for moving from theory to practice in urban schools (Vol. 285). Peter Lang.

13Melaville, Atelia; Berg, Amy C.; and Blank, Martin J. (2006). Community-based learning: Engaging students for success and citizenship . Coalition for Community Schools.